Source of book: I own the complete Tennyson

Portrait by P.Krämer-Friedrich Bruckmann

Even those who are not fans of poetry have heard of Tennyson; although, I must say, many of those cannot actually name one of his poems. However, his name is instantly recognizable, and most can place him in the Nineteenth Century and associate him with the culture of Queen Victoria.

Tennyson’s reputation is well deserved, as he was thoroughly skilled at writing rhythms and pictures and moods. Even his worst poetry shows skill, if not always inspiration. (Given the quantity he wrote, he was bound to have a few duds. All prolific writers have some works that fail to rise to the highest level.)

In some ways, it is odd that I have reviewed Tennyson last of the three greatest Victorian poets, since he is the best known. I read a play by Robert Browning earlier this year, and reviewed Matthew Arnold in 2011.

Since most of the poems in this collection are fairly long, I have decided to link some of them, rather than quote them.

This particular collection was the second book of poetry written by Tennyson, and the one that established his reputation. It contains several of his best and best known works: “The Lotos Eaters,” one of a number of his poems that explore the emotional depths latent in The Odyssey is one of my favorites.

However, I must mention the opening poem. “The Lady of Shalott” can be quoted in part by any fan of Anne of Green Gables. (I have previously mentioned that Anne, particularly as portrayed by Megan Follows, was my junior high crush.)

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

If you can quote this from memory, you may be an Anne fan.

(Interesting note: this is the 1842 version. The original had different wording here, but I think the revised version is better, which may be why it is more commonly seen in print than the original.)

Here is the attempt to re-create the scene in which the body of the lady is floated down the river. (Anne’s quotations are selective, not sequential.)

The poem itself has an interesting form. The stanzas are nine lines long, and are divided into two sections of five and four lines, respectively. The first four lines of the first part rhyme, and the first three of the second part likewise rhyme. The fifth and ninth lines of each stanza not only rhyme, and rhyme with those corresponding lines throughout the entire poem, they end in one of only three words throughout: Shalott, Camelot, and Lancelot. This could easily feel forced, but Tennyson makes it all seem natural and inevitable.

The theme of the poem also fits with one of Tennyson’s favorite concerns: the balance between freedom and innocence. The lady may view the happenings of the world through a mirror only. She can never experience life directly, because of the vague curse. Tennyson perhaps deliberately alludes to Plato’s cave. In this instance, however, the lady does desire to see more than shadows, but it is her undoing. And yet, it is difficult to fault the lady for her actions. (Tennyson’s famous line in his later work, In Memoriam, “‘Tis better to have loved and lost / than never to have loved at all.” comes to mind.) Better, perhaps, to have lived - and died - than never to have lived. Tennyson may well have been describing his own feelings of alienation. He creates art - the magic web - but cannot leave his art to merely live.

The Lady of Shalott (1905) by William Hunt and Edward Hughes

I am half-sick of shadows, said the Lady of Shalott (1915) BY John Waterhouse

Tennyson explores this theme further in “The Two Voices,” another of my favorites from this collection. This poem was originally titled “Thoughts of a Suicide,” and was written shortly after the death of his best friend, Arthur Hallam. (In Memoriam would be his monumental tribute to his friend.) Tennyson was prone to depression, and this catastrophic event brought him to the brink. The poem explores the poet’s thoughts as he hears the voices of his worse and better natures. He questions whether life is even worth living, and the voices argue back and forth about the meaning of life. Is there even a meaning? Is the world getting better or worse? Does that even matter? Ultimately, there is no satisfying resolution. Indeed, pain is endured, not explained away.

“O dull, one-sided voice,” said I,

“Wilt thou make everything a lie,

To flatter me that I may die?

“I know that age to age succeeds,

Blowing a noise of tongues and deeds,

A dust of systems and of creeds.”

As Job well knew, all the “systems and creeds” in the world are just a noise to a man in pain. Tennyson captures the irritation caused when a “comforter” spouts platitudes, whether secular or sacred during a time of grief. Ultimately, his refusal to give in to the easy answers of his own time gives this poem its timeless power.

“The Palace of Art” also addresses the state of the inner self. Tennyson imagines building a palace within his soul, wherein all of the greatness of art and literature can dwell. It is truly an amazing edifice, but Tennyson fails to find the satisfaction he craves, instead finding himself sickened. He wishes to find a form of repentance in a small cottage, and yet, as the poem concludes, he leaves open the possibility that after his soul is cleansed, he may yet enjoy the beauty of the palace, without his pleasure being mere emptiness.

Just a few random excerpts:

I built my soul a lordly pleasure-house

Wherein at ease for aye to dwell.

I said, "O Soul, make merry and carouse,

Dear soul, for all is well".

***

Full of long-sounding corridors it was,

That over-vaulted grateful gloom,

Thro' which the livelong day my soul did pass,

Well-pleased, from room to room.

Full of great rooms and small the palace stood,

All various, each a perfect whole

From living Nature, fit for every mood

And change of my still soul.

***

Then in the towers I placed great bells that swung,

Moved of themselves, with silver sound;

And with choice paintings of wise men I hung

The royal dais round.

For there was Milton like a seraph strong,

Beside him Shakespeare bland and mild;

And there the world-worn Dante grasp'd his song,

And somewhat grimly smiled.

And there the Ionian father of the rest;

A million wrinkles carved his skin;

A hundred winters snow'd upon his breast,

From cheek and throat and chin.

Beautiful language, and unforgettable images. The form also contributes to the experience. Tennyson tweaks the ballad form by lengthening each line by a foot. Pentameter followed by tetrameter, so it feels sort of like a ballad rhythm, but more stately and unhurried. To me, it seemed as if the earthy rush of the ballad was melded with the solemn pacing of the venerable pentameter, fusing sensual emotion with intellect. This ties in perfectly with the description of the palace, appealing alike to emotion and thought.

Loss is a favorite theme of Tennyson’s poems - and he and his friends experienced plenty of it. “To J.S.” was written to his friend James Spedding after the death of Spedding’s brother. It is worth quoting in full.

The wind, that beats the mountain, blows

More softly round the open wold,

And gently comes the world to those

That are cast in gentle mould.

And me this knowledge bolder made,

Or else I had not dared to flow

In these words toward you, and invade

Even with a verse your holy woe.

'Tis strange that those we lean on most,

Those in whose laps our limbs are nursed,

Fall into shadow, soonest lost:

Those we love first are taken first.

God gives us love. Something to love

He lends us; but, when love is grown

To ripeness, that on which it throve

Falls off, and love is left alone.

This is the curse of time. Alas!

In grief I am not all unlearn'd;

Once thro' mine own doors Death did pass;

One went, who never hath return'd.

He will not smile--nor speak to me

Once more. Two years his chair is seen

Empty before us. That was he

Without whose life I had not been.

Your loss is rarer; for this star

Rose with you thro' a little arc

Of heaven, nor having wander'd far

Shot on the sudden into dark.

I knew your brother: his mute dust

I honour and his living worth:

A man more pure and bold and just

Was never born into the earth.

I have not look'd upon you nigh,

Since that dear soul hath fall'n asleep.

Great Nature is more wise than I:

I will not tell you not to weep.

And tho' mine own eyes fill with dew,

Drawn from the spirit thro' the brain,

I will not even preach to you,

"Weep, weeping dulls the inward pain".

Let Grief be her own mistress still.

She loveth her own anguish deep

More than much pleasure. Let her will

Be done--to weep or not to weep.

I will not say "God's ordinance

Of Death is blown in every wind";

For that is not a common chance

That takes away a noble mind.

His memory long will live alone

In all our hearts, as mournful light

That broods above the fallen sun,

And dwells in heaven half the night.

Vain solace! Memory standing near

Cast down her eyes, and in her throat

Her voice seem'd distant, and a tear

Dropt on the letters as I wrote.

I wrote I know not what. In truth,

How should I soothe you anyway,

Who miss the brother of your youth?

Yet something I did wish to say:

For he too was a friend to me:

Both are my friends, and my true breast

Bleedeth for both; yet it may be

That only silence suiteth best.

Words weaker than your grief would make

Grief more. 'Twere better I should cease;

Although myself could almost take

The place of him that sleeps in peace.

Sleep sweetly, tender heart, in peace:

Sleep, holy spirit, blessed soul,

While the stars burn, the moons increase,

And the great ages onward roll.

Sleep till the end, true soul and sweet.

Nothing comes to thee new or strange.

Sleep full of rest from head to feet;

Lie still, dry dust, secure of change.

This is why Tennyson would be a good choice to read during times of sadness. His pain feels real and honest, but his despair isn’t complete, and his empathy is gentle.

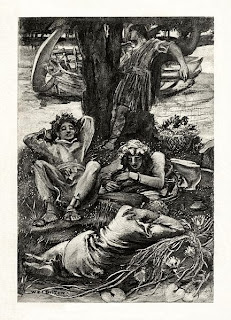

“The Lotos Eaters” takes the story from Homer’s Odyssey, where the sailors eat of the fruit and forget their homeland, wishing to stay there forever. In Tennyson’s hands, we view the incident, not from Odysseus’ point of view, but from that of the sailors themselves. We experience their own conflicts of emotion as they are drawn between their love for their homeland and families, and the peace and joy they feel under the influence of the lotos fruit. During his lifetime, Tennyson was accused of promoting living in an opium stupor, or, alternately, advocating for the rejection of the Christian faith. With enough squinting, either could possibly be read into the text. I didn’t find either idea particularly necessary or helpful in enjoying this work. The poem works because it reflects universal human emotional conflicts. One need not eat a magic fruit to fantasize about a life without responsibility or an end to seemingly endless conflict.

Illustration by W.E.F Britten (1901)

I love the opening lines:

"Courage!" he said, and pointed toward the land,

"This mounting wave will roll us shoreward soon."

In the afternoon they came unto a land

In which it seemed always afternoon.

All round the coast the languid air did swoon,

Breathing like one that hath a weary dream.

Full-faced above the valley stood the moon;

And like a downward smoke, the slender stream

Along the cliff to fall and pause and fall did seem.

And these, dreaming of the ultimate rest from striving and conflict:

IV

Hateful is the dark-blue sky,

Vaulted o'er the dark-blue sea.

Death is the end of life; ah, why

Should life all labour be?

Let us alone. Time driveth onward fast,

And in a little while our lips are dumb.

Let us alone. What is it that will last?

All things are taken from us, and become

Portions and parcels of the dreadful past.

Let us alone. What pleasure can we have

To war with evil? Is there any peace

In ever climbing up the climbing wave?

All things have rest, and ripen toward the grave

In silence; ripen, fall and cease:

Give us long rest or death, dark death, or dreamful ease.

And the stark reality Homer realized: after ten years of war, everything would be irrevocably changed anyway.

VI

Dear is the memory of our wedded lives,

And dear the last embraces of our wives

And their warm tears: but all hath suffer'd change:

For surely now our household hearths are cold,

Our sons inherit us: our looks are strange:

And we should come like ghosts to trouble joy.

Or else the island princes over-bold

Have eat our substance, and the minstrel sings

Before them of the ten years' war in Troy,

And our great deeds, as half-forgotten things.

Is there confusion in the little isle?

Let what is broken so remain.

The Gods are hard to reconcile:

'Tis hard to settle order once again.

There is confusion worse than death,

Trouble on trouble, pain on pain,

Long labour unto aged breath,

Sore task to hearts worn out by many wars

And eyes grown dim with gazing on the pilot-stars.

“The Lotos Eaters” inspired other artists. Edward Elgar set the opening stanza of the “Choric Song” for acapella choir.

Hubert Parry set the entire work to music, but I cannot find a clip of that, unfortunately.

I’ll end on a more humorous note. This is “The Goose,” Tennyson’s take on the legend of the golden egg. At the time, it was politically charged, but can be enjoyed out of that context.

I knew an old wife lean and poor,

Her rags scarce held together;

There strode a stranger to the door,

And it was windy weather.

He held a goose upon his arm,

He utter'd rhyme and reason,

"Here, take the goose, and keep you warm,

It is a stormy season".

She caught the white goose by the leg,

A goose--'twas no great matter.

The goose let fall a golden egg

With cackle and with clatter.

She dropt the goose, and caught the pelf,

And ran to tell her neighbours;

And bless'd herself, and cursed herself,

And rested from her labours.

And feeding high, and living soft,

Grew plump and able-bodied;

Until the grave churchwarden doff'd,

The parson smirk'd and nodded.

So sitting, served by man and maid,

She felt her heart grow prouder:

But, ah! the more the white goose laid

It clack'd and cackled louder.

It clutter'd here, it chuckled there;

It stirr'd the old wife's mettle:

She shifted in her elbow-chair,

And hurl'd the pan and kettle.

"A quinsy choke thy cursed note!"

Then wax'd her anger stronger:

"Go, take the goose, and wring her throat,

I will not bear it longer".

Then yelp'd the cur, and yawl'd the cat;

Ran Gaffer, stumbled Gammer.

The goose flew this way and flew that,

And fill'd the house with clamour.

As head and heels upon the floor

They flounder'd all together,

There strode a stranger to the door,

And it was windy weather:

He took the goose upon his arm,

He utter'd words of scorning;

"So keep you cold, or keep you warm,

It is a stormy morning".

The wild wind rang from park and plain,

And round the attics rumbled,

Till all the tables danced again,

And half the chimneys tumbled.

The glass blew in, the fire blew out,

The blast was hard and harder.

Her cap blew off, her gown blew up,

And a whirlwind clear'd the larder;

And while on all sides breaking loose

Her household fled the danger,

Quoth she, "The Devil take the goose,

And God forget the stranger!"

It’s hard to suggest a bad place to start when it comes to Tennyson. (My kids like “The Eagle.”) This collection is a pretty good place to start. Whether or not you like Victorian poetry in general, it is hard not to enjoy Tennyson’s marvelous use of language and rhythm and the way he makes his words augment his meaning by their very sounds.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)