Source of book: Audiobook from the library

This is kind of a random book that looked interesting to me. I needed an audiobook, and it happened to be available.

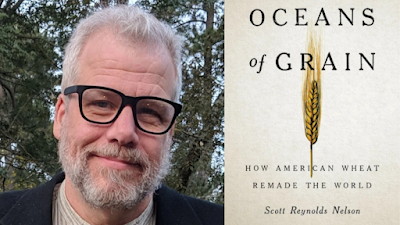

Historian Scott Reynolds Nelson offers as his thesis in this book that the shift from Ukrainian wheat to American wheat to feed the cities of Europe was a central cause of the breakups of empires and eventually the first world war.

But there sure is a lot more in this book than that. It is a history of the wheat trade from prehistoric times through the beginning of the 20th Century, and spans the entire globe.

From the so-called “black paths” that connected the grainfields of the Steppes to ports such as Oddessa, to the conflict (and sometimes symbiosis) between slave-harvested cotton and free-soil wheat. The Black Death features prominently in this book in several different ways, and Potato Blight finds its chapter as well.

While I think at times Nelson may stretch a bit to make everything about wheat, he is correct that everything is connected, and food is the most central issue when it comes to civilizations, empires, and trade.

Since this was an audiobook, and I listen to those while driving, I didn’t get the chance to write down a bunch of quotes or otherwise take notes. I will be relying in this post on my own memory quite a bit - I hope I get the details correct. I will pretty much just mention things at random as recall them.

To start with, I want to talk about Yersinia Pestis, aka the Black Death. This bacterium has its reservoir in the marmots of the steppes. We have marmots here too - I see them regularly hiking at high altitudes - but they don’t seem to have the same close connection to other rodents - and humans - that the Asian ones do.

From time to time, the infected fleas would jump from the marmots to rats, and spread the disease among humans. Because, of course, rats follow the grain, fleas follow the rats, and humans are tasty.

The fun thing about this is that Yersinia can be detected in the bones of people who died thousands of years ago. And the genome can be sequenced and traced to show where outbreaks occurred and how they spread geographically.

Since most humans traveled only a few miles from their homes during the early days of agriculture, the tracks of Yersinia can show the routes of traders back then, and the far distances the plague spread at various times.

These outbreaks were bad enough, but the ones in the Middle Ages seem to have been the worst. Probably due to growing urbanization combined with lack of knowledge about how it spread, it more than decimated Europe.

One of the results of this was that grain production temporarily became more local, which led to (among other political results) the fall of the Byzantine Empire, which depended on revenue from grain going through Constantinople.

Later, a different disruption - the increasingly low cost of ocean transport combined with cheap American wheat - would lead to the fall of a later empire - the Ottoman - and the Russian Revolution.

Potato blight would likewise disrupt economies. Europe’s rural poor had switched to eating potatoes, with wheat largely going to urban elites. When the potato crop failed, the subsequent political failure led to mass famine. In the long term, this rearranged populations (millions emigrated to the United States), disrupted supply chains, and shifted the food balance further towards wheat.

Central to this book are the writings and ideas of Israel Lazarevich Gelfand, better known by his pen name Parvus. Ever heard of him?

He was the forgotten Marxist - we all know about Lenin and Trotsky, but Parvus was arguably every bit as important. His ideas on economics focused more on grain and less on capital, with the idea of imperialism taking the place of capitalism as the central enemy of the working poor.

There are a few reasons he is less known today. In the Soviet Union, his contributions to the Revolution were erased after Lenin came to power - no sense in having competition. There were other complications, of course. Parvus was aligned with Maxim Gorky, who fell out of favor with Lenin. And Parvus was a German agent - although that is more complicated, since the Communist goal was not merely a Russian revolution, but one that would, they hoped, arise in Germany. But with World War One, this became awkward to say the least.

Oh, and there is also the problem that Parvus was Jewish, which, despite Hitler’s conflation of Communists with Jews, led to Parvus experiencing plenty of antisemitism. Certainly Stalin’s later suppression of Parvus’ writings carried strong antisemitic overtones.

The West, too, ignored Parvus. The usual obvious reasons apply to Nazi Germany: antisemitism and anticommunism. For other Western countries, his theories seemed to have all the objectionability of Marxism generally, but with more esoteric theoretical content.

This is too bad, because I found the stuff mentioned in this book to be pretty fascinating, and indeed, perhaps Parvus was the more thoughtful and reality-based Marxist of his time.

The author is a total nerd about this stuff, so the final chapter traces Parvus’ descendants. His son Yevgeny became a Soviet diplomat, was eventually arrested and sent to the gulags by Stalin, but somehow managed to survive to an old age and write about his experience.

His other son, Lev, defected, changed his name to Leon Moore, and had a fascinating career as an adviser to the CIA.

Yevgeny’s daughter Tatiana became a science fiction author, but apparently little was translated into English. The book refers to a particular work of hers which sounds fascinating - robot overlords are disarmed by feeding them poetry, which they can’t understand, and malfunction. One wonders if this will work with AI. Alas, my attempts to find this book were unsuccessful. It probably is long out of print.

As I mentioned, this book is really detailed yet broad. Want to know how different forms of transport affected the grain market? You are covered. Want to hear about banking and finance? You bet you will.

Did you know that both our current use of negotiable instruments (such as checks) and the use of the futures market to create predictable costs and limit risk first arose in the international grain markets? Those are both covered in this book.

How was World War One strategy centered around grain transport? Or, for that matter, how did the different approaches to provisioning armies determine world history? Yes, that too is discussed.

Overall, despite the detail, the book never really drags or gets bogged down. The writing is clear and effective, if not quite as fun as the very best non-fiction writers such as Simon Winchester. The level of detail makes the book thoroughly worth it.

My one complaint is with the audiobook, which has a fairly flat reading. It’s fine, but not one of the better ones. It felt like the reader was just punching the clock, rather than actually interested in the topic. Fortunately, I found the book quite interesting.

No comments:

Post a Comment