Source of book: Borrowed from a friend.

Murakami is weird. And not just weird, weird in many different ways and in different genres. For example, Norwegian Wood is kind of a straight-up realistic love story and love tragedy. But still weird in many places. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is even weirder - a sprawling work with magical realism and flashbacks to the war against Russia in Manchuria. The weirdness wasn’t really explained, either, it just was. So much about that book was left in mystery. Which is not a criticism - if anything, part of the appeal was that it never over-explained.

So, going into Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, I wasn’t sure what to expect, except that it would be weird. And it was.

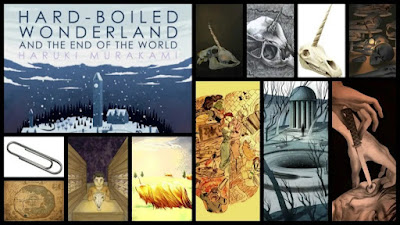

All the images in the collage will make sense once you have read the book...

How to describe it? Well, there are two storylines which alternate chapters - a total of 20 chapters for each story. They are connected, although how and why does not become apparent until the last quarter or so of the book.

The first thread is the “Hard-Boiled Wonderland” - a gritty cyberpunk thriller about a man who works as a human encoder for the corporate “white hat” side of information security. The basic idea being that every code is crackable except the one that nobody understands how the “black box” encoder works, and the best black box device is the human subconscious.

The second, “The End of the World,” takes place in a surreal, fantasy-like place, where unicorns are part of some essential function of a walled town, and nobody has a mind anymore.

None of the characters in the book have names. They get occupations or descriptions, like “The Librarian,” or “The Old Man.” There is a general sense that even though these are individuals, we can never fully know who they are.

In both story threads, the narrator spends much of the book trying to figure out what is going on. The “Calcutec” narrator is summoned to a mysterious assignment from a possibly insane, possibly malevolent scientist, has his apartment torn apart by gangsters, and is starting to have weird visions of an imaginary place. The narrator in The End of the World has recently arrived, and has to figure out what the hell is going on, as he knows - and indeed remembers - next to nothing.

Okay, so, that’s a bit of a setup. But trying to describe just how weird this book is is futile. It has to be experienced, not described. It also goes to some very interesting places. As with other Murakami books, it is never just - or even primarily - about the surface plot. Human psychology and human society are always the deeper narrative. In this case, the author explores the idea of identity. What actually makes us individuals? Is free will real? Is a loss of memory a loss of self? And a lot more besides.

Oh, and plenty of thinking about the meaning of mortality, and a concept of eternity existing in the finity of the mind.

I really should also add, quite funny – the humor is often dark, but wicked and witty.

A few passages stood out in the book, starting with this one about the narrator’s experience being trained (and modified) for his job as a Calcutec.)

“One more point,” they intoned in solemn chorus. “Properly speaking, should any individual ever have exact, clear knowledge of his own core consciousness?”

“I wouldn’t know,” I said.

“Nor would we,” said the scientists. “Such questions are, as they say, beyond science.”

Related is the explanation the narrator finally gets from the mad scientist.

“Each individual behaves on the basis of his individual mnemonic makeup. No two human beings are alike; it’s a question of identity. And what is identity? The cognitive system arisin’ from the aggregate memories of that individual’s past experiences. The layman’s word for this is the mind. No two human beings have the same mind. At the same time, human beings have almost no grasp of their own cognitive systems. I don’t, you don’t, nobody does. All we know - or think we know - is but a fraction of the whole cake. A mere tip of the icing.”

And also:

“Pursue this much further and we enter into theological issues. The bottom line here, if you want t’call it that, is whether human actions are plotted out in advance by the Divine, or self-initiated beginnin’ to end. Of course, ever since the modern age, science has stressed the physiological spontaneity of the human organism. But soon’s we start askin’ just what this spontaneity is, nobody can come up with a decent answer. Nobody’s got the keys to t’the elephant factory inside us. Freud and Jung and all the rest of them published their theories, but all they did was t’invent a lot of jargon t’get people talkin’. Gave mental phenomena a little scholastic color.”

Later, as the narrator and the scientist’s granddaughter escape the sewers below Tokyo (it’s…a long story), he has a fascinating thought about religion.

I was swimming. Orpheus ferried across the Styx to the Land of the Dead. All the varieties of religious experience in the world, yet when it comes to death, it all boils down to the same thing. At least Orpheus didn’t have to balance laundry on his head. The ancient Greeks had style.

There is another philosophical idea housed in an episode at The End of the World. A group of men are out digging a hole while it snows. The Colonel explains this to the narrator.

“Tell me, what is that hole for?” I ask the Colonel.

“Nothing at all,” he says. “They dig for the sake of digging. So in that sense, it is a very pure hole.”

“I don’t understand.”

“It is simple enough. They dig their hole because they want to dig. Nothing more or less.”

I think about the pure hole and all it might mean.

“They dig holes from time to time,” the Colonel explains. “It is probably for them what chess is for me. It has no special meaning, does not transport them anywhere. All of us dig at our own pure holes. We have nothing to achieve by our activities, nowhere to get to. Is there not something marvelous about this? We hurt no one and no one gets hurt. No victory, no defeat.”

I am still thinking about this spin on human futility and the possible meaninglessness of most of our existence. The Colonel makes it into an admirable and positive thing.

I’ll end with another bleak idea, which the narrator considers near the end of the book. He has enjoyed a lovely night and day with The Librarian, mutual sex and pleasure and time together. But he knows his fate, yet chooses not to tell her.

Had I done the right thing by not telling her? Maybe not. Who on earth wanted the right thing anyway? Yet what meaning could there be if nothing was right? If nothing was fair?

Fairness is a concept that holds only in limited situations. Yet we want the concept to extend to everything, in and out of phase. From snails to hardware stores to married life. Maybe no one finds it, or even misses it, but fairness is like love. What is given has nothing to do with what we seek.

Humans are weird about this, right? Nothing in our experience of nature or the universe involves “fairness.” Things just are, whether they are fair or not. It is only within human society that the concept has any meaning, and there it is simply the behavioral relationships requiring mutuality. Yet we apply this to everything, from the “unfairness” of a young kid dying of cancer to whether the traffic lights go our way on the way home from work. I get the feeling that these are the kinds of things that rattle around in Murakami’s brain all the time, and end up making it into his books.

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World was published in 1985, although it wasn’t translated into English until 1991. It is his fourth book, and the one considered to be his first of his mature period. It was the next one, Norwegian Wood, that propelled him to superstardom (to his chagrin), and was the first translated into English for sale outside Japan. (His first novels were translated only for use in teaching English to Japanese students, and were not widely distributed outside of Japan until decades later.)

I should mention that a few of the elements that seem to be present in most of Murakami’s books are in this one as well, although perhaps not as centrally as they would be later. There is the filled in or abandoned well, which may correspond to a bottomless well or sink. There are the constant references to Western music, both classical and popular. There is the uncomfortable sexual tension with a teen girl. There is a sequence involving water or drowning or being buried somehow. And, of course, there is the aching loneliness, which seems to pervade all of Murakami’s books. One wonders if his deep introversion is a factor in this theme.

I find it fascinating that Murakami did not train as a writer - he studied drama, then went on to own a jazz coffeehouse. He came to writing as well as running later in life, but became great at both. For someone who did not set out to become a great writer, his writing is multilayered and nuanced and highly imaginative. And weird. Definitely weird. And that is a good thing.

Trying to recommend a book to start with for newcomers to Murakami, I have no idea what to recommend. All three books I have read have been so very different, yet each is great in its own way.

No comments:

Post a Comment