Source of book: I own this

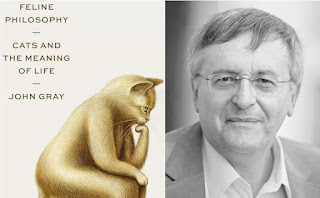

First, let’s get this out of the way: there are a LOT of notable people with the name of John Gray (or John Grey.) This book is by the philosopher John Gray, who is definitely not to be confused with the pop-psychology author of the gender-essentialist twaddle, Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus.

This book combines elements of Gray’s philosophical ideas with, well, cats. Apparently, cats and philosophers have tended to get along pretty well, and there are some insights about human nature that have come as a result of the human/feline interaction.

I am not entirely in agreement with Gray’s philosophy, to be honest. He isn’t a big fan of the idea of free will, or of humans having any ability to determine their destiny. I think he has too rigid of an idea of “human nature” - I’ll discuss that a bit eventually, when I finish another book I am reading. Oddly, reading this book, he reminded me rather a lot of Qohelet, the central character in Ecclesiastes. “Meaningless, everything is meaningless…so live in the moment and enjoy yourselves, not worrying about death someday.” If you are into philosophy, a good way to describe him would be the opposite of John Rawls.

Philosophical differences aside, I actually thought the book was fascinating. Gray clearly has spent a lot of time around cats, and as a fellow cat lover, I think his analysis of feline behavior, emotions, and outlook on life are accurate. There is certainly none of this silliness about cats being aloof and unloving and malevolent - all stereotypes that persist today. Rather, he notes that they adhere to a definite philosophy of life - one that does not bother to worry about the future, that lives in the moment, and accepts things as they are.

In this, cats clearly differ from humans. Humans are, as he correctly points out, haunted by the knowledge of our own death. (Cats do appear to know when they are close to death - and withdraw to do so, embracing death, if you will.) In order to make this bearable, we invent coping mechanisms, either distractions (so we don’t have to think about it) or attempts at immortality through inventing meaning for our lives.

From this starting point, Gray explores the philosophy of cats from several angles. He discusses how cats (unlike dogs) domesticated humans, rather than the other way around. He looks at why cats don’t struggle to be happy - they just are, unless they are in danger or pain at the moment. He looks at the fact that “morality” is something humans do, while cats (and generally other animals, with a few exceptions like our closest relatives) do not think in terms of morality. He examines the way that feline love works - anyone who thinks cats do not love doesn’t know cats. But cats are more realistic about the ephemeral nature of love. He looks at how cats respond to death, and how we might take some inspiration on our own view of the meaning of life from cats.

While the philosophy part can be a bit bleak sometimes, for the most part, this is a lighthearted, affectionate book, combining serious ideas with a deep love for our feline friends. In this, I can sense, despite our other differences, a fellow lover of cats.

Here are some of the ideas that I thought were fascinating.

Cats have no need of philosophy. Obeying their nature, they are content with the life it gives them. In humans, on the other hand, discontent with their nature seems to be natural. With predictably tragic and farcical results, the human animal never ceases striving to be something that it is not. Cats make no such effort. Much of human life is a struggle for happiness. Among cats, on the other hand, happiness is the state to which they default when practical threats to their well-being are removed. That may be the chief reason many of us love cats. They possess as their birthright a felicity humans regularly fail to obtain.

There is definitely truth in there. For example, just think about the tragic and farcical consequences of humanity’s denial that sexuality is a part of human nature. All the unnecessary guilt, all the battles with each other - indeed, all those ludicrous superstitions about masturbation that continue to circulate - and that is just one element of human nature we seem determined to repress. And yes, there is nothing quite as content - indeed smug - as a cat. We do love them because they find a full tummy and a sunbeam to be the meaning of life. Gray talks at more length in a subsequent chapter.

When people say their goal in life is to be happy, they are telling you they are miserable. Thinking of happiness as a project, they look for fulfilment at some future time. The present slips by, and anxiety creeps in. They dread their progress to this future state being disrupted by events. So they turn to philosophy, and nowadays therapy, which offer relief from their unease.

Just to be clear: Gray isn’t dissing therapy as treatment for specific issues, but rather as used in the way people use popular philosophy or religion to treat a general discontent with their human existence. And I do know people who do this (some are related to me…) Gray notes that what humans call “happiness” is often something else altogether. After discussing several schools of philosophical thought; ones which promise to give meaning to life, he puts his finger on the problem.

All these philosophies have a common failing. They imagine life can be ordered by human reason. Either the mind can devise a way of life that is secure from loss, or else it can control the emotions so that it can withstand any loss. In fact, neither how we live nor the emotions we feel can be controlled in this way. Our lives are shaped by chance and our emotions by the body. Much of human life - and much of philosophy - is an attempt to divert ourselves from this fact.

One of the reasons I have rejected the fundamentalist/evangelical doctrine of my upbringing is exactly that. It promises both to give a way of living that guarantees (manipulates) God will like you more than other people, and thus prevent loss - and it insists that it makes any losses that do occur somehow to be part of a cosmic plan and thus ultimately good. And this is just horseshit on a stick. (And worse, when it is used against the victims of abuse, who are expected so say God intended it for their good. That’s just cruel and nasty.) In reality, bad things happen for two reasons. Sometimes, because bad people do bad things to others. But mostly, because shit happens. For most people the bad that happens to them is out of their control, and telling them to just feel better about it doesn’t help anything.

And that eventually leads into one of the best passages in the book, even if it isn’t directly about cats: Pascal’s Wager.

I first heard about this as a kid. (Yes, I was that sort of a kid, which I think is why my parents have struggled with me all my life. I can’t simply accept things “just because.”) The gist is that it is worth making some sacrifices during one’s life on the off-chance that God exists and heaven awaits. I never felt that was convincing at all. And Gray explains why.

First, this assumes that we know which god to bet on. And not just which god, but which theology related to that god, and which set of rituals and rules related to that god. And so on…

Thus, it isn’t just one wager, so to speak, but an entire universe of wagers. And one with terrible odds: you have to guess the one true thing™ that will get you that reward, and, if you guess wrong, you lose. So belief is more like winning the lottery than hedging one’s bets.

Second, what Pascal is really proposing, if you read the rest of his writing, is a diversion. He is terrified of death, so he diverts himself with religion. Gray notes that there are plenty of non-religious ways of doing this that are just as effective.

Third, Pascal is falling into another trap, one that I think is the central, crucial error of Evangelicalism: the belief that what God really cares about is Believing the Right Things™. Get one’s list of doctrines right, check all of those theological boxes, perform the right cultural standards, and you get heaven in the end. This reduces God to the role of a psychopathic pedant, as I came to realize while I was still a minor. (Hence decades of unnecessary battles with my parents over cultural rules for both me and my eventual family.)

I could really do a whole post on this. And on the related question of how Christians could live better lives if they reversed the usual “what if?”: what if there really was no god and afterlife? How would they live if their consciences and internal morality were all they had? (And the judgment of history….who wants to be known as the witch burner?)

In the section on ethics, Gray also examines the problem of morality. Gray does not believe in a universal morality dictated from a supreme being, obviously. He is also skeptical of the Enlightenment concept of “natural law,” originating from a universal human nature. I won’t get into all of what he says, some of which is more convincing to me than others, but I do want to mention the way he contrasts the Western/Christendom/Enlightenment belief system with both the ancient Greek idea of the dike - one’s nature and place in the universe - and the Chinese idea of the tao. Having read the Tao Te Ching a few years ago, this was certainly an interesting discussion. Personally, I have found this idea to be helpful in my own life. Rather than trying to fit my life into rigid conceptions of who I should be, I have been able to function as the person I am. To find my place in the universe based on my own gifting and calling, not the categories imposed from without. As Gray notes, our Western concept owes much to Aristotle, and that is problematic.

According to Aristotle, the best sort of human being was one like himself - male, slave-owning, and Greek - who was devoted to intellectual inquiry. Apart from justifying the local prejudices of his time - a practice nearly universal among philosophers - this view has a more radical defect. It assumes that the best life for humans is the same, at least in principle, for everybody. True, most cannot achieve it, but this only shows their inferiority to those that can. The possibility that human beings might flourish in many different ways, which cannot be ranked in any scale of value, did not occur to Aristotle. Nor did the idea that other animals might live good lives in ways of which humans are incapable.

Taoism again offers a refreshing contrast. Human lives are not ranked in value and the best life for other animals does not mean becoming more like human beings. Each individual life, every single creature, has its own form of the good life.

This has been at the core of so much of the turmoil in our nation, and in my birth family. There is this idea that only one kind of life - the conservative, white, middle class, christian, patriarchal…the list goes on - is a morally acceptable and fulfilling life. When human experience gives strong evidence to the contrary - atheists seem happy and fulfilled and moral, LGBTQ people are happier when they live in accordance with their nature, white people seem the most dysfunctional in our country on average, egalitarians like my wife and I have good marriages - the response is to brutally suppress these truths.

I also want to mention the passage on cruelty. I agree with Gray that cats are not cruel. When we say they are (based on how they hunt and play with their victims), we are projecting our own emotions on what they do.

As predators, a highly developed sense of empathy would be dysfunctional for cats. That is why they lack this capacity. It is also why the popular belief that cats are cruel is mistaken. Cruelty is empathy in negative form. Unless you feel for others, you cannot take pleasure in their pain. Humans displayed this negative empathy when they tortured cats in medieval times.

This is why those who feel (rather than practice) empathy can be infinitely cruel. It is impossible to take pleasure in the pain of others if you do not understand that pain.

Gray explores this idea as well in the chapter on love.

Among human beings love and hate are often mixed. We may love others deeply, and at the same time resent them. The love we feel for other human beings may become hateful to us, and be felt as a burden, a fetter on our freedom, while the love they feel for us can seem false and untrustworthy. If, despite these suspicions, we go on loving them, we may come to hate ourselves. The love animals feel for us and we for them is not warped in these ways.

When it comes to the discussion of death, I thought Gray made a great point (borrowed from Ernest Becker) that human beings chase power so they feel like they are escaping death. And also, that cruelty comes from that same impulse. Active manipulation and control of others gives that illusion that we can control death itself. He also notes that the totalitarian movements of our time are also related to this. Having lost our former rituals easing the reality of death, we embrace both mass movements and this illusion of controlling everything - so we don’t have to face death alone.

I think Gray’s ideas about cats and dying hold up well. For example, I think he is right about this:

If cats could look back on their lives, might they wish that they had never lived? It is hard to think so. Not making stories of their lives, they cannot think of them as tragic or wish they had never been born.

Humans are different. Unlike any other animal, they are ready to die for their beliefs…But if humans are unique in dying for ideas, they are also alone in killing for them. Killing and dying for nonsensical ideas is how many humans have made sense of their lives.

To identify with an idea is to feel protected against death. Like the human beings who are possessed by them, ideas are born and die. While they may survive for generations, they still grow old and pass away. Yet, so long as they are in the grip of an idea, human beings are what Becker called ‘living illusions.’ By identifying themselves with an ephemeral fancy they can imagine they are out of time. By killing those who do not share their ideas, they can believe they have conquered death.

When it comes to the question of “how then shall we live?” Gray makes a list of ideas drawn from how cats live that he thinks can be helpful for humans. A few of these seem like good advice.

One burden we can give up is the idea that there could be a perfect life. It is not that our lives are inevitably imperfect. They are richer than any idea of perfection. The good life is not a life you might have led or may yet lead, but the life you already have. Here, cats can be our teachers, for they do not miss the lives they have not lived.

And this one:

Life is not a story. If you think of your life as a story, you will be tempted to write it to the end. But you do not know how your life will end, or what will happen before it does. It would be better to throw the script away. The unwritten life is more worth living than any story you can invent.

And finally:

Beware anyone who offers to make you happy. Those who offer to make you happy do so in order that they themselves may be less unhappy. Your suffering is necessary to them, since without it they would have less reason for living. Mistrust people who say they live for others.

In the words of another philosopher:

Anyone who is among the living has hope. Go, eat your food with gladness, and drink your wine with a joyful heart. Enjoy life with your wife, whom you love, all the days of this meaningless life that God has given you under the sun—all your meaningless days. For this is your lot in life and in your toilsome labor under the sun. Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might, for in the realm of the dead, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom.

Oh, and go find a cat to pet. A bit of purring will help ease any existential crisis.

No comments:

Post a Comment