Source of book: I own this.

This book was my second selection for Black History Month this year. (The other was Allensworth the Freedom Colony.)

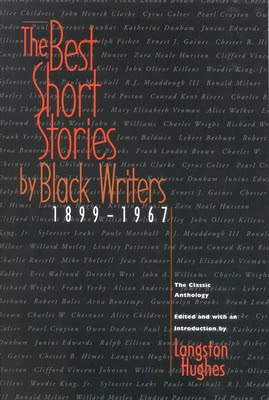

In 1967, poet and writer Langston Hughes, shortly before his death, put together an anthology of short stories by black writers - a “best of” the years 1899 to 1967. At that time, it was entitled The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers, but the title has been updated for the currently in print edition. I purchased a “used” paperback of the reissue.

There are a total of 47 stories, by 47 different authors, arranged roughly in the order of the author’s birth. Charles W. Chesnutt starts things off with “The Sheriff’s Children,” a classic that I had read before, and ends with “To Hell With Dying” by Alice Walker. Some stories are by familiar names, but others are by relatively obscure authors. Women are well represented.

The stories vary widely in topic, setting, characters, and mood. Many touch on racial issues of various kinds, from “passing” to the daily humiliations of living in a white supremacist society. But most striking was the way that the stories bring to life everyday experiences, whether with horror or humor.

The book is solid from start to finish - nearly 500 pages of great writing. I can’t think of any clunkers among the stories, although there are a few that are standouts. Hughes did a great job finding and selecting the stories, creating a collection with tremendous variety and showcasing the talents of several generations of black authors.

At the back of the book there are several pages devoted to short biographies of the authors, which is particularly helpful for the more obscure ones.

There is no way I can discuss all 47 stories, but I made some notes about highlights. Starting with Chesnutt seems logical. I want to mention “The Sheriff’s Children” because I think it is a story everyone should read in school. The plot turns on the fact that the young black man who has been arrested and threatened with lynching is in fact the Sheriff’s son, who he sold down the river as a child. Perhaps the most unbelievable thing about slavery was that men literally sold their own children. I cannot imagine doing such a thing, but I guess I am a liberal commie or something. In an interesting twist, Chesnutt could have passed as a white man, but chose instead to become an activist with the NAACP.

One of the interesting things about this book is that a number of authors better known for their poetry (Hughes included) also wrote prose. I loved “The Scapegoat” by Paul Laurence Dunbar. The story is a humorous account of local politics, and local kingmaker Mr. Asbury. He runs the “Equal Rights Barbershop,” and brings in the black vote. Until he is targeted by a local black attorney who feels Asbury is getting a bit too uppity and encroaching on his territory. How that all sorts itself out is hilarious. I wanted to mention a line, though, spoken by the white judge who is kind of in cahoots with Asbury politically.

“Asbury, you are - you are - well, you ought to be white, that’s all. When we find a black man like you we send him to State’s prison. If you were white, you’d go to the Senate.”

Another humorous story that I loved was “Miss Cynthie” by Rudolph Fisher. The story is about the titular character making a visit to New York City to see her son, who has moved there, married, and become fairly well off. She doesn’t know what he does, though. Her dream for him was that he become a doctor (to care for the body), a preacher (to care for souls), or at least an undertaker, as the next best thing to both.

She is shocked, however, to realize that he and his wife are entertainers - they sing and dance and have become pretty big stars. This is horrifying to her - that stuff is sort of against her religion, and certainly her sense of propriety. She is won over, however, when her son sings the song that she taught him as a child, and she realizes that his music is also hers.

Another heartwarming story is a very brief one by Hughes, “Thank You, Ma’am.” A young boy tries to steal a purse, only to find himself taken in by his intended victim. I love one exchange in particular.

“You gonna take me to jail?” asked the boy, bending over the sink.

“Not with that face, I would not take you nowhere,” said the woman.

“The Revolt of the Evil Fairies” by Ted Poston looks at colorism, in the context of elementary school drama. The school always does a weird version of Sleeping Beauty, with the script written for each year by the teacher. It always seems to involve a battle between the good fairies and the bad fairies. The young narrator notices that regardless of talent, the “good” parts always go to lighter skinned kids. Since the narrator is one of the best, he aspires to more than just a “bad fairy.” But he notices as well that throughout the community, lighter skinned people get the good stuff. The good jobs, the good professions, the better homes. The darker ones are stigmatized from birth, practically. As his friend puts it, “If you black, you black.” The story ends with a hilarious impromptu fight at the end of the play, but the humor does not detract from the central problem.

Another story that takes a hard look at culture is “Almos’ A Man,” by Richard Wright. Dave, a young teen, is frustrated with the lack of respect he gets, so he decides that buying a gun will be the way to get it. This ends badly, of course. But Wright really captures the central stupidity of this facet of gun culture. Dave’s mom asks, why do you need a gun? Well, because anything can happen so we need a gun in the house. This sounds far too familiar to me. As does the “gun gets me respect” thing. In reality, though, as Dave’s mom knows, the people who want guns because they want respect or because “anything can happen” are literally the last people who should have guns.

There are several stories that involve military men, and examine the problem of disrespect toward black soldiers. “Health Card” by Frank Yerby is particularly poignant. Johnny is recently married, and his wife is coming down by train to spend his brief leave with him. Unfortunately, the MPs decide to demand “health cards” from soldiers on leave - proof that they do not have untreated STIs before they go sleep with prostitutes. Johnny doesn’t have one, because he hardly needs one to sleep with his own wife. But he gets harassed by the white MPs, who spit tobacco on his wife’s shoes. He wants to go fight them, but she pulls him to the ground. He sobs, crying that “I ain’t no man.” She makes it clear that she wants him alive, and that she considers him to be not just a real man, but her man. This is a recurring theme in the book - black men treated like trash, and denied the right to retaliate. I wish I could say this is no longer an issue, but I know better.

I wanted to mention an incident in “See How They Run” by Mary Elizabeth Vroman. A young teacher just starting out ends up serving in a rural school - a very different experience from her own privileged and city childhood. Part of her learning curve is figuring out how to teach the more “difficult” kids, those often from impoverished homes, with missing parents, and little background knowledge.

One of the children is named C. T. The teacher, Miss Richards, cannot understand this. How can the name just be the initials? And can anything be done to fix it? I am reminded of my wife’s extended family, because there was a great uncle (or something - I forget all the connections, but this was some time ago) named C. V. Just the initials. The story there, however, is that his dad was named Custer Violet. Dad wanted to pass the name on, but was too kind to inflict the full name on his son. So C. V. it was.

There is another passage in the story that I loved. Miss Richards aspires to teach, not merely keep order. The officious principal wants the children to be kept quiet and sedate, using as much violence as necessary to achieve that result.

Ah, you dear, well-meaning, shortsighted, round, busy little man. Why are you not more concerned about how much the children have grown and learned in these past four months than you are about how much noise they make? I know Miss Nelson’s secret. Spare not the rod and spoil the child. Is that what you want me to do? Paralyze these kids with fear so that they will be afraid to move? afraid to question? afraid to grow? Why is it so fine for people not to know there are children in the building? Wasn’t the building built for children?

Miss Richards determines never to become a disciplinarian.

From now on I positively refuse to impose my will on any of these poor children by reason of my greater strength.

This is something I have been struggling with regarding my upbringing, and also my own parenting. The old habits die so hard. What you learned as a child is so ingrained that even when you know it is wrong, you still do it, you still react out of that. The whole point of “christian” parenting of the James Dobson/Gary Ezzo/Michael Pearl/Bill Gothard belief system is to impose the will of the parent on children by brute force. To break the will of the child. To make them afraid particularly to question. Because that is rebellion.

My parents weren’t full Ezzo, let alone Pearl, but they were very Dobson and Gothard, both of which taught the importance of enforcing unquestioning obedience. I must have been a thoroughly frustrating child, because my will never completely broke, and I pushed back even though I knew the consequences. But I can see now how that ingrown reaction to childish behavior still draws me toward an assertion of the will. God knows, I continue to fight back against the instinct, but the patterns are so hard to break. I can hope that I have done better, at least a little.

In one case, the story is part of a novel. “The Blues Begins” by Sylvester Leaks is one of those. The story is tragic, and looks at the dysfunctional family dynamics of patriarchy combined with poverty. The part I wanted to quote, though, was the opening.

Monday morning came and the blues began: Rent Man Blues, Insurance Man Blues, Washday Blues, White Folks Blues, and Got-damn-it-don’tcha-mess-wit-me Blues!

One of the more unusual settings was “Barbados” by Paule Marshall. Set on that island, it is a psychological drama of an old rich black man who hires a young girl as a servant. She wants to be treated as more of an equal, at least in the sense of humanity, but he is too tied to his status to notice. There is a particularly great line when he tries to get her to go home every night rather than sleeping in the small closet she has appropriated. He tries to get her to take her pay and leave, but she doesn’t.

[W]ith a futile gesture he swung away, the dollar hanging from his hand like a small sword gone limp.

I love the double (or is it triple?) entendre there. The trifecta of male posturing. The dick, the dirk, and the dollar.

“The Day the World Almost Came to an End” by Pearl Crayton is another humorous story, about a girl who convinces herself the world is ending. I love this line in particular:

In spite of the fact that my parents were churchgoing Christians, I was still holding on to being a sinner. Not that I had anything against religion, it was just a matter of integrity.

There are a couple of stories involving France that bear mentioning. James Baldwin is such a phenomenal writer, and his story “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon” is amazing. It is about a black man who has been living in France as an ex-pat, marries a Swedish wife, has a kid, and is now returning to America as a successful musician. But he knows he is potentially in for a whole lot of shit. The story is mostly about his own fears and hopes rather than action.

The other, “Old Blues Singers Never Die,” by Clifford Vincent Johnson, tells of an encounter in Paris between the blues singer River Bottom and a young soldier. The whole story is great, but how about this line?

And that big depression, what was that? It didn’t say nothing to no colored man because he hadn’t known nothing but depressions.

I’ll end with a line from later in the story. A character is described as being “too proud to smell his own shit.” That’s a great line, and we all know exactly what it means. We know those people.

There are so many more stories I could have highlighted. I strongly recommend this collection not just for Black History Month, but because it is a truly great anthology of short stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment