Source of book: Borrowed from the library

This book is one that I never expected I would read. I sure doesn’t sound like my sort of book, on the surface at least. Let’s look at the issues:

Social lives of upper-middle-class white people from New England? Eh, not really my cup of tea.

Relationship drama, involving an ex-wife, another divorce, and a teen going bad? I get that at work already.

College application counselors? Eh.

AirBNB drama? What even is that?

Gay culture in San Francisco? Maybe I guess?

Lots of irony, detachment, and snark? It can get old pretty quickly.

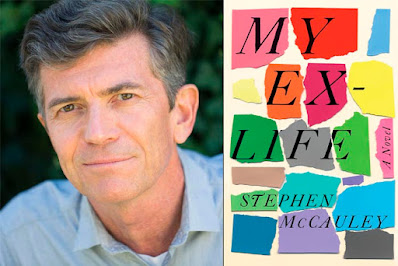

But then, I discovered this book via NPR, when the author gave an interview, and he made his book sound actually interesting. I put it on my list, and gave it a try.

And, despite the potential issues, I actually really liked this book.

McCauley based the premise of the book on a series of conversations he had with other members of his gay men’s running group. While he himself came out in college, a number of his friends took a while to realize that what they felt for women wasn’t sexual or romantic. And, by this time, they had wives, and sometimes kids. This used to happen a lot, by the way. Back when even secular sorts tended to look at LGBTQ+ people with suspicion, coming out was a tough thing, tougher than it is now (although in some families, it is still unthinkable.) As McCauley notes, it isn’t that hard to mistake other positive attractions - friendship, admiration, affinity, emotional intimacy - for romantic love, particularly if you deeply want to be in a heterosexual family. It can even work for a while, but tends to fall apart.

So, the setup: David and Julie were married years ago, briefly. She got pregnant, but lost the pregnancy. Soon afterward, David has a relationship with the husband of one of their friends, and both he and she have an epiphany about his true self. They divorce, and love on opposite coasts for two decades. Meanwhile, Julie remarries, and has a daughter, Mandie. But, things don’t work out there either. Julie is divorcing again, Mandie is struggling for motivation to apply for college, David is losing his lease in San Francisco, and, well, things take a turn nobody expected.

Since David’s job is as a “college application counselor,” it is easy for Julie to call him up to help out. He flies out to New England, and, well, they kind of become a family again, in a way.

So, can David also find a way to scrape together enough funds to cash Julie’s soon to be ex husband out of the house? Can David get through to Mandie? And what about the neighborhood feud over AirBNB rentals?

Yeah, on paper, that sounds kind of boring. But it isn’t, at least the way McCauley writes it.

A good part of the charm in this book is the self-deprecating humor. David is very much a stand-in for the author, with his OCD-level organizing, his dismay at his aging body, his weakness for Thai takeout, and his particular way of being gay. McCauley pokes fun at himself, I mean David, for a lot of the book, and David’s inner thought world is delightful. (The book switches points of view throughout, between David, Julie, and Mandie. It is in third-person throughout, though: just the perspective changes. Also, was this a linear narrative? How did that sneak past the editors?)

The same applies to McCauley’s satirical look at a certain sort of bourgeois gay culture. It really is funny, but it doesn’t feel mean-spirited at all, unlike the sort of vicious anti-gay humor that is still all too prevalent. It is definitely the difference between outsiders laughing, and insiders giving a bit of a wink.

Also in for a laugh is the world of competitive college entrance essay writing. David is good at what he does, but the occasional stories about his clients are wicked funny. For what it is worth, my kids are starting out at the local community college, rather than trying for status with a big-name school. It seems to all of us like a better investment, particularly since the majors they want are readily available from state schools. I also think that this would be a better destination for Mandie, given her lack of motivation and the tight funds, post-divorce.

One of the things that struck me about the book was how ordinary everything was. Notwithstanding a bit of a deux ex machina at the end, everything that happens is just mundane and everyday. Not that much “happens,” in the dramatic sense. Both the conflicts and the resolutions are mild, and the sort that we can all imagine in our own lives. The drama level is almost surprisingly low - these are not high drama people generally.

I wrote down quite a few lines, and I hope that these will work out of the context of the book. Other lines, I skipped, as much as I loved them, because context was everything. Despite the ironic tone, the writing is good in a simple and understated way. One might even call it “tasteful.”

David wasn’t good at making money with money, and he was suspicious of people who were, especially when they did it with other people’s money, an activity equated with plagiarism.

Or this one:

Men’s obsessions with their own masculinity were embarrassingly effeminate.

True that. If you have to obsess about it, maybe you are proving you don’t have it. Kind of like the enormous brodozer in our neighborhood a few years back, with a huge “size matters” sticker on the back window. Some people feel compelled to advertise their, um, shortcomings.

There are certain things in life you must expect to pay for - electricity, dry cleaning, sushi. Past the age of fifty, a younger lover with a perfect ass must, realistically, be added to the list.

Some of the comments on American culture are pretty witty too. This pretty much explains my difficulties in even making small talk with right wingers these days.

Last winter had been mild, but complaining about New England winters was the only truly safe topic of conversation with guests. Accurate or not, it offended no one. Accuracy was beside the point lately anyway. Among a certain segment of the population, acknowledging the existence of scientific data was considered unpatriotic, akin to acknowledging the existence of gun violence unless perpetrated by Muslims or racism that didn’t involve a white person losing a job to a person of color.

I also loved the depiction of Julie’s narcissistic mother, and the decades of passive-aggressive letters. One particularly good line:

“I feel terrible your learning disability wasn’t diagnosed earlier,” her mother had written. “We took you to many specialists, but of course in those days, there was considerably less literature on the matter. If there had been, you might have been able to pursue the academic career your father and I had always planned for you instead of the roundelay of sad marriages and pointless drifting that your life has been. And just to reassure you, darling, we were always proud of the way we accepted the reality of who you are, even though it was so far from what we had hoped.”

Ouch. The thing is, that is only a very slight bit over the top. That last line, in particular, hits a bit close to home. Kind of the thing that wasn’t entirely said, but still made clear, about how my mom felt about my wife. And about how she dealt with her own disappointment at who Amanda was, and how far she was from the dream.

A truly fascinating discussion in the book is about the nature of David and Julie’s relationship. He is staying in a room of her home, and they seem in some ways still like a couple. The things that were good during their marriage still are. Sure, sex is off the table, but…

“They’ll probably assume we’re a couple. And by their standards, we are. Most of them brag about sleeping in different rooms and not having had sex since the nineties.”

That’s a zinger. And, I do tend to wonder, might it be true in certain circles particularly? There are plenty of reasons to stay married in such a situation, as long as both parties are okay with either celibacy or an open relationship. I’m no expert, but I suspect this goes on in upper-middle-class more than you think. There is another scene, later in the book, that muses on the idea that later in marriage, either you kept sex going on a weekly basis, or you stop. “The middle ground of fucking twice a year was grotesque.”

There is a description of two women at this cocktail party they go to. They have husbands, but the friendship is longstanding and has its own relationship dynamic.

Maureen and Sheila had an established routine of quips and mild insults, one more dominant, the other the more frequent butt of jokes. All couples start off as Romeo and Juliet and end up as Laurel and Hardy.

Speaking of snark, there is a couple staying at Julie’s (under the table) AirBNB, who take pictures of dishes at the local restaurants, and make snide comments about it.

A mound of cottage cheese, a slab of steamed fish, a ball of mashed potatoes. “It’s all the same color,” Helene had said incredulously several times. “No color at all. Do you think they do it on purpose? Maybe it’s an art project?”

The people who drift through the AirBNB throughout the book are interesting, even if they only get a mention. Particularly sad is the old woman who is “visiting” her son and his family. Because they see each other only briefly and a few times over the week she is there, before she suffers a stroke. We never learn enough about her to know why there is a semi-estrangement, but whatever the cause, there is sadness in her loneliness.

One of the pivotal scenes in the book - even though next to nothing happens - is when Julie and David have Julie’s ex and his new girlfriend over for dinner. In the run-up, David sorts through his impressions of Henry, including the question as to whether he is homophobic or not. This leads to a bit on David’s brother, who, while not openly homophobic, essentially considers heterosexual happiness as somehow more worthwhile than homosexual happiness. I think for a lot of pre-Trump conservatives, this was kind of the default. (Now, of course, open hostility is back on the table…) I thought this passage was interesting.

He was familiar with this type of man, since many of the successful fathers who hired him fell into that category. It wasn’t that they believed he shouldn’t have the same civil rights as everyone else, it was just that their body language and mildly condescending gazes conveyed the impression that they considered themselves inherently superior. They didn’t want you to be unhappy, they were just convinced that in the grand scheme of things, your homosexual happiness counted for less than their heterosexual joy. David’s brother, Decker, was one of these: he was fine with the fact that David had the right to vote, he just thought David should have the decency not to exercise it.

It was a question of masculinity, of course, but this made no sense to David since he’d come to believe that the libidinous excesses of gay men expressed male desire in its purest form. This made them more genuinely masculine than their heterosexual counterparts, even if they sometimes went overboard with eyebrow-shaping and mid-century sofas.

And, in the same context:

Among the many hypocrisies of the “religious” was the fact that they viewed god as omnipotent, but treated him like a ventriloquist’s dummy by putting their words and crackpot beliefs, prejudices, and unfounded biases into His mouth whenever it suited their purposes.

Whether Henry is like this is an open question - he seems mostly like the sort of person he is - he works in investments. Yeah, fill in the blanks for yourself. McCauley gets a bit of a dig in at Henry’s new girl, Carol, who is one of those “fitness cult” sorts.

In the living room, Carol was explaining to Julie the particulars of her Fitbit. It calculated steps and calories and heartbeats and other statistical information that was essentially meaningless to anyone, even Carol. Americans were increasingly addicted to information, especially when it could be used in support of opinions that were inaccurately described as facts. David supposed that the numbers spit out by the device on Carol’s wrist supported her obsessive need for exercise, a neurosis masked as a virtue. Julie was listening with rapt fascination, not, David knew, because she was interested in the details but because she was astonished that Carol was.

Of the gay culture snark, here is my favorite:

Renata had also sent a photo of the couple renting the apartment, a dour pair that were a cross between an urban, homosexual American Gothic type and a couple of elderly priests impatiently waiting for cocktail hour.

That, and the scenes with Kenneth, the only other gay guy in town, apparently. The lovely thing about the book in this regard is its casual centering of the story around the gay protagonist in a way that brings out the ordinariness of gay existence. It is like the sort of book that just treats, say, African Americans as ordinary people in their own lives, rather than letting injustice be the center. (Nothing wrong with civil-rights oriented books, of course, but the normalization is important too, and wonderful to see more of these days.)

Renata, the real estate agent, is pretty funny, although she wouldn’t see it that way. I do think this line is particularly good.

“We didn’t have vegans when I was your age, dear. We had macrobiotics. I don’t know where they all went. We didn’t have gluten intolerance, either. We had hypoglycemia. I’ll bet you’ve never heard of that.”

Oh yes, I remember the 1980s and the health trends back then. One reason I never went for the whole “everyone is gluten intolerant” nonsense. Been there, done that, got the shits from enough diets over the years.

The subplot of Mandie is interesting. She gets caught up in an an “OnlyFans” sort of thing, but much more dodgy. McCauley said he based the subplot on the experience of a daughter of a friend, which is why it seems quite plausible. The most important takeaway, of course, is that teens should absolutely avoid older men. This would be the most important sex advice I would give my kids. Date someone your own age or close. And a decade is not close.

Before she leaves for her last year of high school (at a different school in a different town, after all the fallout from things), she slips her completed college essay under Julie’s pillow. The essay isn’t important, although it is interesting. What is important is this:

She imagined her mother reading it that night when she got into bed. She thought probably she should say all this to her face, but her mother was so hurt and disappointed, it was hard to say anything to her. And sometimes it was good to commit things to paper.

And this is the thing, despite the snark and the irony and the satire, at the core, this is a bit of an old-fashioned positive book. It harkens back to a time of problems that could be solved with a bit of love and understanding, and the idea that family matters. The modern twist - if it even is modern - is that we aren’t talking about the 1950s nuclear suburban family. Instead, this is an extended family structure, with exes and new partners, with different sexualities and personality styles. But still, a shared commitment that everyone - David, Julie, Henry, and Carol - and also some neighbors and friends and…the village, one might say - that cares enough about each other and about Mandie to find ways to make things work.

As I said at the outset, nothing about the surface of this book would have seemed like my kind of thing. But it actually worked, and I rather enjoyed it.

No comments:

Post a Comment