Source of book: borrowed from my kid

My second kid has been fascinated by Japanese literature for a while - and is taking all of the Japanese courses available as a college student as part of a likely double major. (Their main major will be something in the area of environmental science, but the exact term varies by school and focus.) This book was a Christmas present to said kid, and I was duly informed thereafter that it was one of their favorite books, and I should definitely read it, etc.

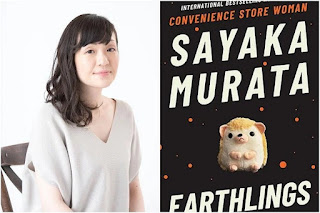

And, for that matter, we had already read and discussed a few other interesting books in translation recently, including Convenience Store Woman by the same author. (Also, The Vegetarian by Han Kang.) And also, a few stories in English but with a Japanese connection: Pachinko by Min Jin Lee (also read for our book club), and A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki.

I am flattered that my adult kids still want to read and discuss books with me - I am a very blessed man indeed.

Earthlings has a lot in common with Convenience Store Woman in its view of society, but takes a very different approach. In the latter, the protagonist chooses to become the ideal cog in the corporate societal machinery, embracing the mindless repetition and quantifiable tasks of the convenience store. In Earthlings, in contrast, the protagonist decides to reject the whole idea of “The Factory” - see below - and live a transgressive life. This eventually leads to some really crazy stuff, including behavior that, ironically, ends up reinforcing the predatory nature of society, just without the candy coating.

The narrator, Natsuki, starts out as a traumatized child. She is the younger child in a family where the older sibling is worshiped, and Natsuki is scapegoated - abused really. This culminates in an incident where a teacher molests her, and her parents refuse to believe her. Natsuki takes matters into her own hands, and brutally murders the teacher, while in a dissociative state.

Natsuki is exceptionally close to her cousin Yuu, who is essentially the only family member who understands her, except maybe an uncle. Yuu has his own issues: his divorced and suicidal mother uses him as a replacement for a husband, a level of emotional incest that is weirdly common in Christian Patriarchy, but obviously exists outside of it as well.

Both Natsuki and Yuu escape from their unpleasant realities into a fantasy world, where they are aliens from a distant planet, stranded until their mothership returns to rescue them.

This fantasy is interesting, because it seems a natural outgrowth of the feeling of alienation from the rest of society. It also is a bit disturbingly similar to some of the theological teachings popular in my former subculture - we True Believers™ are not really of the “world” at all - we are aliens stranded here until Jesus comes back to rescue us and incinerate everyone else. It is a tempting fantasy, particularly for those with a feeling of alienation.

Ironically, I believe that most humans experience this feeling of alienation to some degree or another. We assume everyone else feels a sense of belonging that we do not, we assume others are happier, or more successful, or at least less filled with doubt. And yet, studies indicate that most humans experience doubt, alienation, and imposter syndrome.

I don’t want to give away too many spoilers from the book, but I do want to discuss Natsuki’s idea of The Factory.

From her viewpoint, society is essentially a factory, and humans - “earthlings” - are expected to fulfill two related roles in it. First, they are to create economic value through work - the “factory” of making things. Second, they are to manufacture new humans through childbearing. This burden falls mostly on women, but men too are shamed if they fail to fulfill this role.

In addition to the molestation and murder, there are some other turning points. Natsuki pressures Yuu into having sex with her (as fairly young children), leading to their separation for many years. Natsuki, having no desire for sex or children, decides to deflect the social pressure on her as a woman in her 30s by entering into a platonic marriage.

I had no idea there was a website (in Japan at least) for people to find marriage partners but without sex, but apparently there is. Natsuki finds a husband, and they marry. They sleep in separate rooms, and make their own meals, do their own housework, and so on. No sex. No children.

This cannot go on indefinitely, however, without the families becoming suspicious of the lack of children. And then Yuu reappears, and Natsuki and her husband take a vacation to the old family home where Yuu is living, and things go utterly to hell.

And I mean that pretty literally. The book, which up until that point had at least been fairly realistic, if a bit weird, goes into crazy territory, with incest, cannibalism, and autophagy. The laws of physics seem to be suspended, and the book ends on a bit of a cliffhanger.

I have kind of mixed feelings about the book.

Murata’s writing style is intentionally very flat - very unemotional. Which works well, actually, for what she does with her stories. It also hits some perceptive emotional notes that are more devastating because of how flatly they are stated.

I also think that there is some insight in her view of society. I am by no means an expert on Japanese culture, but at least from the outside, it appears to be undergoing a significant crisis. Birth and marriage rates (and even friendship rates) have plummeted, the population is aging, rural and small town areas are becoming depopulated, and yet the culture continues to be resistant to change. The combination of a culture of long work hours, patriarchy, and hostility to outsiders has crashed headlong into increasingly feminist views of younger women. Without a more egalitarian and family-friendly work culture, many women are simply opting out of motherhood.

This isn’t just a Japanese problem, obviously - you can see it repeating in Korea, and in Poland, and in Russia, and other places with official hostility to feminism colliding with the needs of a post-industrial society.

In Earthlings, you can very much see the social friction. Natsuki wants to be able to live a meaningful life, but does not see meaning in being a corporate cog, or in being a wife, or in being a mother. For her, returning to the Eden of her childhood, and living ferally in nature, represent the kind of “authenticity” she seeks. In reality, though, this Eden turns out to be hell, and the friendship without social expectations is every bit as brutal - maybe more so - than the trappings of civilization.

So, overall, a lot of interesting ideas in the book, and the writing is good.

Where I find myself having an issue is with the vision of isolation and alienation being some combination of inevitable and even desirable. Humans are, generally speaking, social creatures. That is our superpower. We need connection - at least the overwhelming majority of us.

That need for connection cannot simply be reduced to “romantic love is a biological conspiracy to get us to mate.” Otherwise, childless marriages wouldn’t exist, or they would be desperately unhappy. My own experience being around people I know is that in fact childless marriages (sex included!) are often very strong. The bond isn’t there just for “biology” but for the benefits it brings to the entire organism, so to speak.

I get that Murata is neurodivergent and asexual and experiences this differently. She even has gone so far as to say she dislikes food and eating, which is seriously foreign to me, although I know people like her. For me, the idea that no human relationships are really worth salvaging (which is why the need for the shared delusion of being aliens is necessary) doesn’t ring true. So maybe I am part of the “factory” for enjoying my marriage and kids and even sometimes my job? I guess that is a possibility.

If you haven’t experienced Murata, I would recommend Convenience Store Woman as a start. Earthlings is fine for the strong of stomach (you have been warned), but I didn’t find it quite as focused or successful in its ideas as the other book.

No comments:

Post a Comment