Source of book: I own this.

Regular readers of this blog will know that I am a fan of both Henry James and William James. Henry James was one of the greatest novelists of all time, in my opinion, writing such masterpieces as The Wings of the Dove. William James was a luminary in two fields, writing a tremendously influential work on psychology, and contributing to the field of philosophy with his Pragmatism, which is probably the closest viewpoint to my own philosophy.

Those two are well known, but the family itself was fascinating, and had a lot more talent than just Henry (Jr.) and William. One wonders what might have been had the parents not played favorites and been able to look beyond the sexist beliefs of their era.

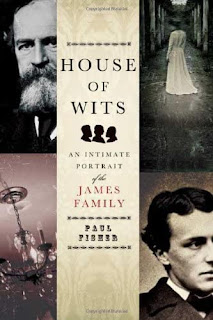

This rather long and detailed book examines the James family, and brings to light a more complex and fascinating picture of a troubled yet close-knit family that gave birth to genius.

Henry James Sr., the father, was the son of a wealthy but controlling man, who attempted to disinherit him. The will was not upheld by the court, however, and Henry Sr. ended up essentially independently wealthy. Which was probably a good thing, because he never did find a vocation that worked for him. He dabbled in philosophy and theology, hit the lecture circuit like his friend Emerson, and published a bunch of stuff that was mostly incomprehensible and unsaleable. He also dragged his family on extended trips to Europe, which proved to be quite influential on the courses of the lives of his children.

In addition to his difficulties in finding a vocation, Henry Sr. also suffered from depression, a mental illness that would go on to afflict all of his children to some extent. He self medicated with alcohol for a while, although he eventually managed to kick the habit later in life. Oh, and he had a leg amputated as a teen, after an injury trying to fight a fire. So, his life was a bit tough even as his financial privilege gave him other advantages.

Holding the family together were Henry Sr.’s wife Mary, and Mary’s sister Kate - whose very brief attempt at marriage ended badly.

This is just a bit of background to the family situation. The book is obviously far more detailed.

There were five children. William, the eldest, was always his father’s favorite, and the one Henry Sr. was sure was the most promising child - the only one he thought had any real ability. However, William struggled to support himself for years, slaving away as a professor on low wages, and only later gaining the fame that his father was sure he would attain. Henry Sr. never saw this success.

In contrast, Henry Jr. - the one we now know without the “Jr.” part - was the one child to attain success relatively early in life. Even so, he didn’t become famous until his 30s, and his books, while critically acclaimed, often sold poorly. His other writings - short stories, criticism, travel articles, plays - contributed to his income.

The other two sons, Wilkie and Bob, seemed to be afterthoughts in the family. They were always expected to go into commerce and earn their own living, unlike the two privileged older boys. In addition, since William had numerous physical ailments, and Henry Jr. suffered an injury to his back that would give him issues for the rest of his life, neither was able to serve in the Civil War. Wilkie was badly injured in the war, and was never quite right again. He died in his 30s of kidney failure. Bob survived injury, but buried himself in alcohol, which destroyed his marriage and probably contributed to his death by heart attack. One wonders what either of them might have been with some family support and encouragement.

The fifth child was the only female, Alice, who seems to have been every bit as intelligent as her older brothers, but without a socially acceptable outlet. In addition, she was unsuited for marriage for a variety of reasons, not least of which appears to have been her sexual orientation. She spent over a decade in a “boston marriage” with another woman, although due to the family’s general reticence about sex, it is not clear where on the continuum between friendship and sexual partnership the relationship fell. Late in life, Alice wrote a diary, which was finally published to some acclaim after Henry Jr.’s death. Unfortunately, Alice too died an untimely death of breast cancer. During her lifetime, she was, as the author puts it, one who men would continuously overlook and underrate.

The James’ family relationship to sex was, to put it charitably, complicated and difficult. William suffered from impotence, likely related to his anxiety disorder and depressive tendencies. Henry Jr. was probably attracted to men, but never appears to have been in a real relationship. Indeed, his careful avoidance of attachment seems to have been his relationship style, although he had close friendships with both sexes. Ironically, he wrote brilliantly about sex, although in a very oblique style, requiring a lot of reading between the lines. And also, sex never goes well in his books. (Seriously, the “hate sex” scene in The Wings of the Dove is haunting and brilliant and enough to make anyone a bit scared of sexuality.)

I already mentioned Alice and her long-term relationship. Apparently Henry Jr. accepted the relationship and was the one sibling that Alice remained close to her entire life. But he also used it as inspiration for the “boston marriage” in The Bostonians, which isn’t exactly a flattering portrayal of such a female-female pairing.

It isn’t difficult to see where these three got their hangups, looking at their parents. Whether Mary would have been functional in another relationship is an open question, but Henry Sr. had enough dysfunction for two.

The book covers the lives of all the members of the two generations - parents and children - but focuses much more on the earlier years, and not much on the careers of either William or Henry Jr. The focus is on the family, not on the works of the two luminaries, as these stories are already well known and written about.

At 600 dense pages long, this isn’t a quick read, but it is well researched, quotes extensively from the numerous surviving letters from the family, and gives a compelling portrait of a very human and complicated family.

There is an observation in the introduction that really stood out to me, because it to a degree describes my own life and marriage. The James family was caught between the rigid Victorian beliefs about gender, and an increasingly influential feminist movement. And, as it played out, this conflict was part of the family dynamics.

The elder Jameses counted as a somewhat unconventional couple - Mary James the more forceful and practical character, Henry Senior more emotive and sensitive - who still embodied quite a bit of Victorian propriety. To their children, they offered both rigidity and veiled permission to be different. Raised with their father’s obsession with “manliness” and his disdain for women as anything but homemakers, the young Jameses had to work hard to carve out identities for themselves, and their rich solutions to these questions reflect many of our contemporary concerns.

My wife and I fit that mold - she is more forceful and practical, while I am definitely more sensitive and emotive. That’s who we are. At least I don’t get hung up on supposed “manliness,” and she has the opportunity in our modern world to have a career and vocation and a chance to use her talents outside the home.

The rest of that fits a bit too, though. Both of us were raised in a subculture that has an obsession with “manliness” and gender roles. I was raised with that kind of weird mix of rigidity and permission to be different - a permission that seems to have gone away in recent years, unfortunately. Both of us worked hard to carve out our own identities.

In that vein, I should mention the book’s description of Mary’s upbringing, in the sort of quintessentially American kind of dysfunctional religion that still dominates our politics today.

The Murray Street Church typified the contradictions of Mary’s upbringing and indeed of an 1830s America that frequently combined austere Calvinism with rank materialism.

The elder Jameses ended up with a belief system that fit neither organized religion nor atheism, which is kind of where I find myself too. In the case of Henry Sr., this was inseparable from his miserable experience with his strict religious father.

Even after his father’s death, Henry’s conflicts with this formidable man had continued to feed the intensity of his heretical religious views. He would have a lifelong dislike for arbitrary authority.

Yeah, me too, even if my own parents weren’t in the same category of controlling as Henry’s father, our conflicts have created a lifelong dislike for arbitrary authority.

Henry Sr., though, would end up imposing his rigid ideas on his children as well. Particularly his views about women, which made things difficult for Alice.

Henry envisioned the adolescent woman as an adjunct to her mother and aunt - a patient, self-sacrificing component in his own emotional support system, who was expected to listen patiently to his visions, tirades, and obsessions. He couldn’t understand why Alice, often confined to the house, was sometimes unhappy and disappointed; her mother certainly never did.

This was, unfortunately, all too common of a belief, and one that still lingers in the “stay at home daughter” movement. Young women as a key part of the emotional support system for needy men. It wasn’t just Alice, either, who was unhappy with this role. So many Victorian wives (including William’s wife, coincidentally named Alice herself) suffered from depression which was very likely directly connected to their repressed roles as support systems for men.

Another interesting bit in this book was also about a retrograde idea that still lingers. Henry Jr. attended Harvard, but found it dull. In general, the coursework at Harvard at this time was all about polishing aristocratic young men, rather than giving an up to date education. Heck, math wasn’t even an elective course at first, and when it was offered, it was the level that my kids did in third grade. Henry preferred to read modern literature, while Harvard’s most modern literature course focused on Chaucer, written over 400 years previously. I mean, even Shakespeare was too modern?

This idea lingers in the form of so-called “Classical” education, with a return to an emphasis on Latin and Greek as the supposed foundation of a “good” education. That this hearkens back to an era when education was a way of preserving class boundaries is not coincidental, which is why it tends to be pushed by groups that also oppose racial equality and gender equality (see: Doug Wilson.) I think it is a good idea to be skeptical when someone insists that some past way of doing things is superior. Are they really doing it because they think that reading Homer in the original Greek trains a brain better than anything else? Or are they doing it because of a belief in a [largely imaginary] glorious past, when things were as they should be? Or because they think of their kids as superior to everyone else? Or because they don’t want to engage with modern ideas and insights? (Particularly, those insights by people who are not white, European, or male?) Often, looking at their beliefs regarding equality will answer the question.

The Jameses were never content to just live in the past, although they remained fairly conservative in their own lifestyles. One of Williams aphorisms seems to describe the family pretty well.

“Genius, in truth, means little more than the faculty of perceiving in an unhabitual way.”

One of the interesting things about reading a book like this is to realize just how connected the Victorian literary world really was. The Jameses were friends of the Emersons, as previously mentioned. But so many other luminaries are in this book. Henry Sr. was part of a club that contained great men in both the literary and scientific worlds, and Henry Jr. followed in his footsteps, making connections to other authors and editors who eventually would aid his breakthrough as an author. In particular, William Dean Howells, well known as an author in his time, but little read today, would publish Henry’s stories in The Atlantic, then a magazine just beginning to become prestigious.

The book is populated at the margins with a lot of assertive, vibrant, interesting women. These include a cousin, Minnie Temple, who tragically died of tuberculosis at a young age like so many back then. Alice, of course. Constance Fenimore Woolson, grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper and an author in her own right. She was a close friend of Henry Jr. for years, and they shared a villa for a couple years in what was a bit of a scandal. (It was not likely a romantic liaison, whatever the tabloids wished.) And also the women that William, Wilkie, and Bob married.

Henry Sr. remained a sexist about all of these women, complaining that they had a “pernicious flaw,” that of an “obstinate will.” Strange how women insist on asserting themselves, as if they were human or something. (Sarcasm, I hope that is obvious. I married and love a woman with a very strong will of her own.)

Not that Henry Sr. was unique. As the author puts it:

Victorian men, addled with their own form of the virgin-whote complex, longed for women to embody both virtue and wantonness - though rarely the same woman at the same time.

Yep, one of my least favorite legacies of the Puritan/Victorian sex hangups. Which still subjects women to denigration as “sluts” for the offense of owning their own bodies and sexualities - or even having independent lives outside the control of men.

The discussion of Alice’s relationship with Katherine Loring was interesting. The one family member who was willing to openly surmise a sexual relationship was William’s wife, Alice, who in general was far more comfortable with discussions of sex than anyone else in the family. The idea of the “boston marriage” was one of ambiguity, and remained so in significant part because it challenged Victorian views of female sexuality.

If females, after all, lacked sexual drives and desires - as the Victorian world wanted fervently to believe - their menages could harbor no amorous or sexual complications. What “improper” interest could two genteel spinsters past marrying age possibly have in each other?

Even now, 150 or more years later, we have a hangover from this idea that females lack a sex drive, leading to, among other things, a neglect of female sexual fulfilment.

The younger generation was not immune from these retrograde ideas either. And others. Late in life, when Henry Jr. finally returned from England to visit New York, he complained that it had changed too much for his taste. Some of these “changes” were real: the skyscrapers and the loss of quaint single houses, the 20th Century bustle, and so on. But his complaint about immigrants was based in a mythical past that never existed.

As he tried to get used to the new Manhattan, Harry took refuge in a nativist fantasy of the past. He recollected a purely white, genteel, Anglo-Saxon New York that had never really existed, even in Ward McAllister’s social register. Contrary to this myth, “aliens” had built New York; through the centuries the city had been a roiling entrepot of class, ethnicity, and race. New York’s jostling heterogeneity had in fact stood out even in Harry;s parents’ days. Its class conflicts had shown in the Panic of 1837 and exploded in that theatrical dispute turned uprising, the Astor Place Riots of 1849. In fact, both frictional and harmonious racial and ethnic diversity had dominated the city since the days of the first dirty wooden taverns and assertive step gables of New Amsterdam, with its tropic-burned Dutch traders, its ubiquitous black servants and freedmen, and its astonishing parade of polyglot sailors. Of course, Harry’s own ancestors hadn’t qualified as Dutch or English “founders”; they were immigrants themselves. The Jameses had come from boggy Ulster, the Walshes from wind-scoured Scotland.

This is the myth that nativists believe - and it is a complete myth. There was never a time when the United States was “pure” - unless you count the times before 1492. The white “race” itself is a myth, a cultural construct created to justify oppression and inequality. The US has always been polyglot, particularly the cities. And those who whine the loudest about present-day immigrants invariably come from groups who were previously considered dirty and undesirable. So, definite marks against Henry Jr. (aka Harry) for these retrograde ideas.

There are a few other observations about the book I wanted to mention. First, every time I read books about this era, I am again struck by how many people died young of what are now preventable or curable diseases. William nearly died of Smallpox. One of his children died of Pertussis (whooping cough). Many died of tuberculosis, or measles, or polio. It is likewise horrifying to see some of these diseases making a comeback, particularly those which were nearly eliminated by vaccines.

I was also amazed by the fact that Henry Jr. wrote so many letters. While many were destroyed or lost, some ten thousand survive - ten thousand! In addition to his novels and stories and so much else. I don’t even have all his fiction yet, and it takes up two feet of my library.

The last bit I want to mention is the close relationship between Henry Jr. and William. The two of them lived most of their adult lives separated by the Atlantic Ocean, although William visited from time to time. They wrote a lot, however, and cared about the other’s opinion. Interestingly, they didn’t see eye to eye on each others’ art. Henry wasn’t really into philosophy, and thus found William’s books to be both brilliant…and boring. William, in turn, complained that Henry’s fiction was too complex and indirect. In one letter, he advised Henry to “sit down and write a new book, with no twilight or mustiness in the plot, with great vigor and decisiveness in the action, no fencing in the dialogue, no psychological commentaries, and absolute straightness in the style.” I can only say that I am heartily glad that Henry ignored this advice.

These are just a few highlights of the book, and I feel I am leaving so much out. This book will primarily be of interest to fans of Henry, William, or Alice James, although as the psychological study of an upper-middle-class Victorian American family, it is fascinating in its own right. It helps to understand where Henry and William came from, in order to put their writing in context. The book itself occasionally seems gratuitously long, but the details also contribute to a fuller understanding of the family and its time.

No comments:

Post a Comment