Source of book: I own this

One of the big epiphanies in my spiritual journey of the past two decades was the growing realization that I am a Humanist. Specifically, I am a Christian Humanist. Whether secular or religious, the core values of Humanism are a belief in the inherent value and dignity of all humans, a belief in both freedom of the individual and a responsibility toward other humans and our society and environment. Humanism stands for human rights, civil rights, social justice, rational thought, participatory democracy, and equality.

While one can certainly make the argument that the very first Christian Humanist was Jesus Christ, it is generally agreed that the Christian Humanist movement started during the Renaissance. A number of figures, mostly in Northern Europe, began to call for reform of the Catholic Church, speaking out against the widespread corruption and greed - the very same issues that led to the Protestant Reformation.

While somewhat parallel to Protestant ideas, Christian Humanism had its distinct differences. The emphasis wasn’t primarily theological, to start with. Christian Humanists (although they wouldn’t recognize that term) focused instead on the practice of Christianity, reconciling doctrine with the great works of ethics produced in antiquity. In this sense, it was a blending of religious and secular ideas like Aquinas did in a more theological and philosophical sense. But it was also a return to the idea of Christianity as a practice, not a belief system or a set of rituals.

The natural conclusion of this movement was that it was a core part of Christian practice to seek the common good, to emphasize love of neighbor and ethical behavior rather than enforcement of rules. It is easy to draw a straight line from the early Humanists to the social justice movements that would follow, from the establishment of a constitutional monarchy with religious tolerance in England to the Bill of Rights in America; from the first wave Feminists to the Abolitionists and Civil Rights protesters. Humanists drew a clear line between themselves and those who sought to maintain hierarchies. To be sure, not every implication of Humanism was fully realized from the start, but the thread runs from the beginning to the present.

In the list of luminaries of the dawn of Christian Humanism, two names stand out. The first, Sir Thomas More, is often familiar to many, either through his Utopia, or from the various movies made about his life. His famous battle with Henry VIII over Henry’s divorce and break from the Catholic Church ended in his execution, which is pretty dramatic stuff. He is also given some fantastic lines about immigrants in Shakepeare’s contribution to Sir Thomas More - lines that are so recognizably Humanist 400 years later.

The second name, while less familiar for some reason, is the greatest Humanist of his era, hugely influential, and still worth reading today: Desiderius Erasmus. It is difficult to overrate his contributions to thought and policy. His translations of the New Testament into Latin and his more comprehensive Greek editions opened questions of translation that still are debated today. His writings on free will pushed back against John Calvin and Martin Luther, and still influence our understanding of freedom. His writings on education of both children and adults influenced the movement for universal public education a century later. And, perhaps closest to my own heart, his belief in freedom of thought and belief, free from religious compulsion, lies at the core of the freedom of religion and separation of church and state that we take for granted.

In Praise of Folly is Erasmus’ best-known work, although it is not his most serious or detailed. The book was dedicated to Sir Thomas More - the two were friends and shared a dry sense of humor, and More likely appreciated the pun of the book title. (Moriae Encomium, the Latin title, is a pun with the double meaning “in praise of folly” and “in praise of More.”) In the book, Erasmus pokes fun at the foibles of society, organized religion, and superstition. It is very good-humored, deliciously sly, and full of great lines. Like many others of my sort, I would consider the world Erasmus envisioned as a true Utopia - and indeed, the things I love most about the world I live in are the same things that Erasmus helped bring into existence.

My edition of this book is a hardback from 1942, part of the “Classics Club” editions by Walter J. Black, Inc. I have a handful of these, all purchased used here and there for next to nothing. The only sour note about the book is that it never says which English translation it uses (and also, arcs over consonant blends, like “st.”), although I assume it is an old one given the archaic language. What I really do love about the book is that it includes a short biography of Erasmus by Hendrik van Loon, and wry illustrations by the same. I wasn’t that familiar with Van Loon before I married my wife: she brought two of his books to our home library. Apparently, in addition to being a respected historian (who emphasized the role of the arts in history), he won the very first Newbery award. His biography takes up about a third of the book, and is really excellent and fun to read, so I am glad it is there. A bonus book.

Anyway, I made notes from both books, and I will start with the Van Loon biography.

Van Loon opens the biography with a riff on the fact that he is getting older, and has read most of the best books. Like Erasmus, he is tongue in cheek and rather amusing. Here is a bit of it:

I have also become aware of a gradual decline in the violence of those devastating emotions which caused an otherwise sensible citizen to waste so much time upon the pursuit of certain ideals of female pulchritude which were apparently unattainable on this faulty planet of ours. But these disturbing passions are now being replaced by certain far more satisfying sentiments of true comradeship and sincere affection which are the reward of that rather bizarre quest for the One Perfect Individual.

Van Loon notes that he can never recreate that feeling he had when he first discovered Erasmus, but he hopes that first-time readers can experience the same thrill.

It so happens that I revere that memory. For whenever I am asked in what kind of world I would like best of all to live, my answer is all ready: “Turn me loose in a universe re-created after the Erasmian principles of tolerance, intelligence, wit, and charm of manner and I shall ask for no better.”

Me too. Which is why I am horrified by the turn toward cruelty, hate, and stupidity that the American Right has taken over the last few decades.

Van Loon also notes that Erasmus wrote this book during the Inquisition - how could he not have been scared? Even today, some of the sentiments would have been met with opposition. But, as Van Loon points out, the Church wasn’t yet feeling threatened. People just assumed Christianity, and a little internal criticism wasn’t yet the internecine (and political) wars and bloodshed that would eventually wrack Europe for a couple centuries. Luther had not yet made his break, and few thought that Christendom would literally split.

In spite of the somewhat antiquated language of this little book, which we have retained on purpose, that you may understand the old gentleman all the better, you will be struck by the surprisingly “modern approach” of one who has been in his grave for more than four centuries. And in the second place, you will throw your arms up in great and serious astonishment and you will exclaim, “But this cannot be true!” No one in his senses would have dared to write this sort of thing at a moment when the Inquisitor was in his heyday and when no one was safe from the spiritual Gestapo of the sixteenth century…Even today such a furious blast against established authority would hardly be tolerated. But we no longer burn those with whom we disagree; we merely leave them to the mercies of a very cheerless economic fate.

Erasmus was, like a surprising number of luminaries of the past, an illegitimate child. This idea that in the past, people didn’t have sex outside of wedlock is ludicrous, and Van Loon (Dutch like Erasmus) points out all the ways that people got around the rules in very practical ways. For example, a woman who had illegitimate kids could marry their father, and conceal the children at the wedding under a “Cloak of Chastity,” and when the kids were revealed after the ceremony, they would be accepted as legitimate. (There is a box to check on the divorce forms here in California to accept pre-marital children as of the marriage - the modern version…)

As an adult, Erasmus fell in with a group of clerics who, while not monks, pursued a form of religious community, seeking to live out their faith in practice. Van Loon points out that these groups have always been viewed with suspicion. The Romans distrusted the early Christians because they shared possessions, and likewise, “socialist” sects continue to be distrusted by the religious authorities.

The cruel eradication of the Albigensians in the Middle Ages was the result of a popular crusade against their pernicious heresy of regarding all Christians as common not only in the sight of God but also in that of the dispensers of tangible treasures. The Anabaptists of the first half of the sixteenth century were no doubt a good deal of nuisance with their cult of the nude and their other absurdities of behavior. But in order to enrage the populace against them as “enemies of society” and bring about those disgusting lynching parties which fill so many of the most disgraceful pages of the history of that disgraceful era, all the magistrates of any given city had to do was to let it be whispered about that those fiends believed in sharing the wealth in common.

Sounds like our current era, doesn’t it? People freaking out about anything that makes distribution of wealth more equitable, and calling it “socialism.”

I like Van Loon’s line regarding Erasmus’ teaching.

Expose normally intelligent boys and girls to an inspired teacher who can give them a real curiosity about the world they live in, and in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred they will do the rest themselves. Give them a key and show them where the lock is, and after that leave them alone.

That’s kind of the good sort of homeschooling in a nutshell. It is also the reason this blog exists - it is a record of my own exploration, carrying on the thirst for knowledge that I learned from the inspired teachers of my youth.

The Renaissance was a time of profound cultural change - much like our own - and dreamers like Erasmus dared to imagine a new, better world, that could be created out of the ruins of the old one. It is this hope that keeps people like myself going in the times we are in.

Let us remember that Erasmus like ourselves lived in an era when an old world, an old form of society, an old culture, was slowly disappearing from view while the new one had not yet made its appearance with sufficient clarity to allow anyone to predict its shape, color, and inner substance. Erasmus, therefore (and very much like ourselves), was doomed to spend his days in an age of uncertainty and of doubt, when all the old values were being revaluated into new ones and when the verities of today might be exposed as the falsehoods of tomorrow. For feudalism was dead or dying and a new class of people were appearing upon the scene to take the place of the old masters.

I also think Van Loon has a profound observation about all Utopias, from Plato’s Republic on down:

The writers of Utopias and those philosophers who have meditated upon the Ideal Form of Government have always been inspired by some concrete example of government, with which they themselves were familiar. They had of course idealized their model.

Thus, Plato envisioned an idealized Athenian democracy, Augustine saw a religious version of the Roman Empire, and, as Van Loon opines, Erasmus modeled his on a small Dutch village.

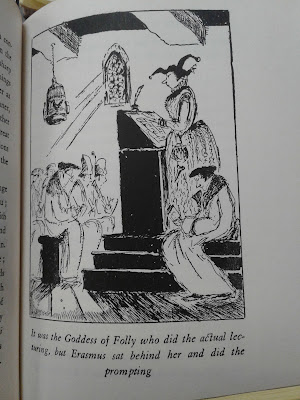

So, that much is the biography and introduction. In Praise of Folly is in the form of an enconium, a well known classical form that Erasmus could assume his readers knew well. In this case, Folly takes the pulpit and praises herself. Which is as humorous as it sounds. But also, she makes some really great points. After all, all men are fools, and there is nothing more human than to be foolish and pursue folly. Along the way, Erasmus slyly calls out a host of the usual suspects.

The Stoics are a recurring target, and I think that one could put Puritans in the same category.

For even the Stoicks themselves, that so severely cry’d down pleasure, did but handsomely dissemble, and rail’d against it to the common People, to no other end but that having discourag’d them from it, they might the more plentifully enjoy it themselves.

Folly (and thus Erasmus) also makes a very modern point about “self-love.” In Erasmus’ view, it is a healthy thing to accept and embrace who you are, rather than defer to societal standards of, say, beauty. We must accept and love ourselves before we can receive love and commendation from others.

Elsewhere, Erasmus also notes that “happiness” is subjective. If a man loves something that others consider inferior, how is his happiness any different? I may prefer Mahler, but others are into Kid Rock. Is my pleasure truly better or greater? Maybe. But not necessarily.

That said, Erasmus pokes fun at himself and other “wise men.”

Invite a Wise man to a Feast and he’ll spoil the company, either with Morose silence, or troublesome Disputes.

And that leads to my favorite line in the book:

And therefore if the more foolish a man is, the more he pleases himself and is admir’d by others, to what purpose should he beat his brains about true knowledge, which first will cost him dear, and next render him the more troublesome and less confident, and, lastly, please only a few?

Sigh. This is what we see all around us. In the Trump Era, willful ignorance makes one admired by others. Why bother actually knowing anything, when you can just express a nasty bigoted opinion and your tribe will cheer you?

My second favorite quote is this one. Folly laughs off the idea that she should be jealous of the other gods, and the worship they receive, while she is laughed at.

Then do I conceive my self most religiously worshiped, when everywhere, as ‘tis generally done, men embrace me in their Minds, express me in their Manners, and represent me in their Lives; which worship of the Saints is not so ordinary among Christians.

Yeah, not too many supposed Christians actually embrace the teachings of Christ in their minds, and act accordingly. But Folly, well….

I wish I could quote the entire chapter entitled “Now Watch Our Great Illuminated Divines.” It deals with the ridiculous theological disputes and how theologians get so caught up in disputes about trifles that they miss the entire point. Indeed, he notes, Christ and the Apostles themselves clearly didn’t understand the nuances of doctrine. Some of these doctrinal disputes look hilarious to us today, but they were a freaking big deal once. Others are still with us, and still as stupid as ever. I am sure we too will have our doctrines that seemed to mean so much to us now, that later generations will scratch their heads at how we ever cared.

I will quote one bit, though, that is really hilarious. If you actually read the Bible, it is striking how little of what is believed about Hell is actually in there. In fact, in my opinion, the only way you could read the Bible and believe that a literal Hell exists is if you had a lot of cultural baggage from, say, Dante, in your head already. (And a bit of the old Greek myths too…) But it is astonishing how detailed of a mythology about Hell our theologians have created.

Then for what concerns Hell, how exactly they describe every thing, as if they had been conversant in that Common-wealth most part of their time!

Yeah, it really does seem to me that certain preachers seem to be far more familiar with Hell than with anything good. Perhaps it is because they fantasize about inflicting Hell on others, and thus have spent a lot of time imagining it. Hell is the projection of the evil in their hearts.

In the following chapter, Erasmus turns to monks and the various orders.

In a word, ‘tis their only care that none of ‘em come near one another in their manner of living, nor do they endeavor how they may be like Christ, but how they may differ among themselves.

Erasmus goes on to note that this is an impoverished form of religion, so far removed from Christ’s “Precept of Charity.” And this really is the hell of the fundamentalist cult I was in. We spent so much time trying to be different from “the world” - meaning anyone outside the cult. We had to dress differently, listen to different music, read different books, and so on. There was no interest in actually being like Christ - just being different from other people.

Erasmus has no patience for politicians either. He describes a certain type in a way that very much fits Trump and the American Right.

And now suppose some one, such as they sometimes are, a man ignorant of Laws, little less than an enemy to the public good, and minding nothing but his own, given up to Pleasure, a hater of Learning, Liberty, and Justice, studying nothing less than the public safety, but measuring everything by his own will and profit; and then put on him a golden Chain, that declares the accord of all Virtues linkt one to another…

Near the end, Erasmus also gets a point in about religious tolerance.

What authority there was in holy Writ that commands Heretics to be convinced by Fire rather than reclaimed by Argument?

This is the problem currently facing religion though, isn’t it? They are failing miserably at convincing by argument. So is fire the only thing left for them?

Erasmus ends with a humble thought: at the bottom, all men are fools, even the very best. And that is okay. Christ didn’t come to those who had it all together, but for those who needed healing. So, lighten up, be tolerant and kind, and realize nobody knows everything.

No comments:

Post a Comment