Source of book: I own this.

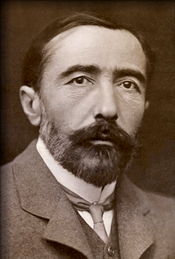

Conrad

is one of those individuals that I find amazing for unlikely

achievement. Born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski in 1857, in the

Ukraine, but to a family of Polish nobility, he managed to become one of

the most highly regarded English authors. This despite not attaining a

fluency in spoken English until his 20s, and waiting until his mid-30s

to switch from his maritime career to writing.

His

parents took part in the resistance movement, seeking to throw off

Russian domination of both Poland and the Ukraine. As a result, they

were both exiled to northern Russia when Conrad was a small child. Both

would die of privation and tuberculosis by the time their only child was

eleven. He was then raised by a maternal uncle, until departing for

training for a seaman’s career at sixteen. Since Conrad showed no

interest or skill in academic pursuits - although he was an avid reader -

his uncle figured he needed to learn a trade. He also seemed to have a

knack for languages, learning French, German, Latin, and Greek: a useful

skill for a merchant sailor.

As

the son of a dissident, he could not well return to Russia, so he

sought foreign citizenship, eventually becoming a British subject and

rising to the level of Captain in the Merchant Marine.

But

for a fortunate meeting, he might have been a footnote in the ledger of

the annals of the British Empire. On one of his voyages, he met a

discontented young lawyer named John Galsworthy, who was himself

considering a career change. As a result of this meeting, both resolved

to seek their fortunes in literature. Both would go on to success, and

the literary world may be forever grateful for this fortuitous meeting.

Conrad

is generally a pessimistic author, and things do not typically end well

for his characters. While this was not particularly popular in his

time, it was influential on later generations of writers. Furthermore,

the Twentieth Century played out in a way that followed his dark vision

far more than the optimism of the late Victorian period. Removed from

their time and technology, his books could easily represent our own

times.

The Secret Agent was written toward the end of the early part of Conrad’s writing career, in 1907, before he gained a real literary reputation.

The

title character, Mr. Verloc, is a lazy double agent of sorts. He is not

a glamorous James Bond type, but a man seeking to make a living to

support his wife, her mother, and her half-wit brother. To this end, he

nominally runs a shop selling goods of dubious legality and morality,

while working as an agent for the Russian embassy in London. At the same

time, he also serves as an informant to the local police force.

These

two jobs were not really in opposition in practice, however much they

might be in theory. Verloc’s job is to infiltrate and inform on a local

anarchist cell, which both the Russians and the London police wish to

keep in check.

Compared

with the far more successful Communists, the Anarchists never really

accomplished enough to gain a significant following in the United

States, although they were a key factor in the Spanish Civil War. (See

my review of the excellent The Cypresses Believe in God.)

They came to my attention a few years ago with their rather bungled

protests of the World Trade Organization. While not a major factor in

the last fifty years, they were once a force nearly as feared as the

Communists themselves.

(Quick

primer: Anarchists believe in the complete destruction of both

government and all authorities and hierarchies. Many support the use of

violence and destruction to accomplish this. While this much is agreed,

the various branches of Anarchism differ as to what should replace the

status quo. Some support complete collectivism resembling Socialism or

Communism. Others envision a libertarian society. Still others believe

that once the current institutions are destroyed, a new society will

spontaneously arise, a kind of utopia perhaps. All of these viewpoints

find their homes in characters in this book.)

Conrad

uses the Anarchists as the basis for his plot, in the process giving a

remarkable picture of their beliefs and goals. Impressively, he does

this using very little of the book, sneaking it into the conversations

of the characters in a minimum of space, never interrupting the

narrative enough to bog it down.

The

inciting event occurs soon after the opening. Mr. Vladimir, who works

for the embassy, has become Verloc’s new boss. He demands that Verloc

earn his keep by arranging for a bomb to be set off at the Greenwich

Observatory, which would then be blamed on the Anarchists, leading

(Vladimir hopes) to the British people suspending their pesky belief in

the rule of law and simply liquidating the Anarchists without proof of

overt acts. Verloc knows that this is not at all in his line of work,

and he further knows that the motley group of “revolutionists” that

meets at his apartment lacks anyone with both the nerve and the desire

to do it. In theory, these are dangerous men, but in practice, only the

“Professor,” who manufactures explosives, poses any danger in reality.

And the Professor has no intention of getting his own hands dirty: he

is, after all, the only one who can make bombs.

As

becomes rapidly obvious, this cannot possibly end well. And, indeed, it

ends in “success” for the authorities, the disgrace of Vladimir; but

the utter destruction of the smaller players in the drama. The attempted

bombing goes horribly awry; and an inexorable destiny leads to a

stabbing, suicide, and insanity.

Along

the way, Conrad takes jabs at both the Anarchists and the hierarchies

they seek to destroy. Mr. Verloc himself is of the Establishment, as he

muses early on.

He

surveyed through the park railings the evidences of the town's opulence

and luxury with an approving eye. All these people had to be protected.

Protection is the first necessity of opulence and luxury. They had to

be protected; and their horses, carriages, houses, servants had to be

protected; and the source of their wealth had to be protected in the

heart of the city and the heart of the country; the whole social order

favourable to their hygienic idleness had to be protected against the

shallow enviousness of unhygienic labour.

What

I particularly love about this passage is that he cuts right to the

heart of class snobbery. The great “unhygienic” masses.

Also in that vein is Conrad’s description of the wealthy patroness who supports Michaelis, the formerly imprisoned Anarchist.

A

certain simplicity of thought is common to serene souls at both ends of

the social scale. The great lady was simple in her own way. His views

and beliefs had nothing in them to shock or startle her, since she

judged them from the standpoint of her lofty position. Indeed, her

sympathies were easily accessible to a man of that sort. She was not an

exploiting capitalist herself; she was, as it were, above the play of

economic conditions. And she had a great capacity of pity for the more

obvious forms of common human miseries, precisely because she was such a

complete stranger to them that she had to translate her conception into

terms of mental suffering before she could grasp the notion of their

cruelty.

…

She

had come to believe almost his [Michaelis’] theory of the future, since

it was not repugnant to her prejudices. She disliked the new element of

plutocracy in the social compound, and industrialism as a method of

human development appeared to her singularly repulsive in its mechanical

and unfeeling character. The humanitarian hopes of the mild Michaelis

tended not towards utter destruction, but merely towards the complete

economic ruin of the system. And she did not really see where was the

moral harm of it. It would do away with all the multitude of the

"parvenus," whom she disliked and mistrusted, not because they had

arrived anywhere (she denied that), but because of their profound

unintelligence of the world, which was the primary cause of the crudity

of their perceptions and the aridity of their hearts. With the

annihilation of all capital they would vanish too; but universal ruin

(providing it was universal, as it was revealed to Michaelis) would

leave the social values untouched. The disappearance of the last piece

of money could not affect people of position. She could not conceive how

it could affect her position, for instance.

Lest

one think that Conrad sympathises with the one side of the issue, there

are corresponding passages in which he skewers the beliefs of the other

characters in turn. None escape either his mockery or his sympathy.

For

example, “Toodles,” the (unpaid) personal secretary to the Home

Secretary (equivalent to our Secretary of State), has socialist ideals.

But he never lets these ideals interfere with his desire to hobnob with

high society.

Toodles

was revolutionary only in politics; his social beliefs and personal

feelings he wished to preserve unchanged through all the years allotted

to him on this earth which, upon the whole, he believed to be a nice

place to live on.

The

characterizations are really the most memorable part of this book. The

plot is necessary to reveal the characters, but they never are there

just to serve the plot. The plot takes the shape it does because of who

the characters are, and how they react to bad circumstances and worse

luck.

Verloc, of course, is well drawn.

Mr.

Verloc would have rubbed his hands with satisfaction had he not been

constitutionally averse from every superfluous exertion. His idleness

was not hygienic, but it suited him very well. He was in a manner

devoted to it with a sort of inert fanaticism, or perhaps rather with a

fanatical inertness. Born of industrious parents for a life of toil, he

had embraced indolence from an impulse as profound as inexplicable and

as imperious as the impulse which directs a man's preference for one

particular woman in a given thousand. He was too lazy even for a mere

demagogue, for a workman orator, for a leader of labour. It was too much

trouble. He required a more perfect form of ease; or it might have been

that he was the victim of a philosophical unbelief in the effectiveness

of every human effort. Such a form of indolence requires, implies, a

certain amount of intelligence. Mr. Verloc was not devoid of

intelligence - and at the notion of a menaced social order he would

perhaps have winked to himself if there had not been an effort to make

in that sign of scepticism. His big, prominent eyes were not well

adapted to winking. They were rather of the sort that closes solemnly in

slumber with majestic effect.

The

others of the Anarchist cell are interesting individuals. Michaelis,

released after a lengthy prison sentence for serving as a locksmith in a

prison escape that went wrong, who becomes a mystic and, as it were, a

saint; content in his belief in the inevitability of the Revolution.

Karl Yundt, the fiery old man - who has never actually lifted a finger

in action. Ossipon, the lecherous and hunky young man, who lives more to

leverage his Anarchism to aid him in bedding women than in taking any

personal risks. The Professor, short and unimposing, who attempts to

compensate for the lack of respect he gets through firmness of will -

who carries a bomb in his vest at all times to prevent arrest. The

authorities also are memorable. The Chief Inspector, who would much

rather be chasing burglars, who abide by a recognizable code. The Home

Secretary, who seems more concerned with arcane domestic issues than

terrorism. The Assistant Commissioner, who was forced to leave his

preferred employment in Colonial Asia because of his marriage to a

controlling woman.

The

complex relationships between the members of Mr. Verloc’s extended

family are also well drawn. Verloc himself fancies that he is loved

simply for being himself, but the reality is more complicated. Mrs.

Verloc intended to marry a poorer man, but was prevented because she was

weighed down by her crippled mother and mentally challenged brother.

She considers it her duty to make provision for their support. Thus,

Verloc is primarily important to her because of what he represents as

both breadwinner and as a father of sorts to her brother. When things

unravel, these expectations lead to a tragic and violent end.

The Secret Agent formed the basis for Alfred Hitchcock’s early film, Sabotage.

It was also adapted to film in a more faithful version in 1996. This

scene between the Professor (Robin Williams) and Ossipon (Gerard

Depardieu) in the cafe preserves most of the original dialogue, and is

remarkably faithful to the original. And, the score is by Phillip Glass.

The cello solo (played by Fred Sherry) undergirding this scene is

stealthily sinister. (Note: I haven't seen this movie, so I assume it takes liberties elsewhere, but this scene at least is well done.)

No comments:

Post a Comment