Source of book: I own this.

One of my legal colleagues retired last year, and did some downsizing. The upside of this was that I inherited a bunch of cool books. My second kid stole all the Ursula LeGuin for her collection (and ended up writing an English paper about her) but most of them have joined my collection.

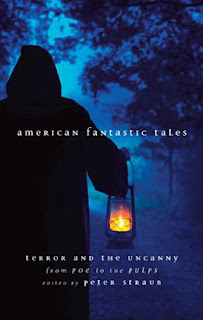

One of those was a two volume box set from Library of America edited by Peter Straub. (Author of Ghost Story, which we read for our book club.) The stories are presented in chronological order by year of publication, so this first volume is subtitled “Terror and the Uncanny from Poe to the Pulps,” and covers 1805 to 1939. This is quite a spread in terms of time and writing style, from the Early National period with Charles Brockden Brown and Washington Irving, to the Romantic Era of Poe and Hawthorne and Melville, all the way through to the dawn of the modern era.

Peter Straub selected a total of 44 stories for this volume (713 pages), each by a different author. In doing so, he made some fascinating decisions. First, for famous authors like Poe, he chose a less famous story. So, we get Poe’s “Berenice” rather than, say, “The Tell-Tale Heart.” There are exceptions, such as “The Yellow Wall Paper,” but for the most part, the best known stories are absent. Straub also selected a number of lesser known authors, including a fair share of women. This, despite the fact that for most of the time period, writing was not a respectable profession for women. In general, the variety of authors and stories is pretty broad, so the book never feels repetitive.

Another good feature of the book is the short biographies of each author at the back. Since many of them are unfamiliar, this was helpful to understand the stories.

The first two-thirds or so of the book consists of authors who were not particularly connected to each other by genre, which is how you get Sarah Orne Jewett, Bret Harte, Henry James, Willa Cather, and F. Scott Fitzgerald in the same book. This is because horror hadn’t become the genre that it eventually did become. Many earlier writers wrote in a variety of genres, with horror or mystery or supernatural or suspense being just one of the types of stories they wrote.

By the 1920s, however, pulp magazines - particularly Weird Tales - brought the genre together, and spawned a generation of writers dedicated to its particular type of story. Most of the authors in the book from the 20s and 30s contributed to Weird Tales, and often got their start writing for the pulps.

It would be too much to say something about every one of the 44 stories individually. There were some highlights. Some of these I have read before (I have read all of Poe’s stories, for example.) but a good number were new to me. Some of the authors were also new discoveries. For example, Lafcadio Hearn, who introduced the United States to Japanese culture. (And he also married a Japanese woman, which was a huge scandal 1890. Oh, and before that, he was briefly married to a former enslaved woman, but they separated when he was unable to remain employed once their story came out.) The story chosen for this book is “Yuki-Omna,” one of the Japanese ghost stories he collected and translated.

Nathaniel Hawthorne makes an appearance, naturally, with “Young Goodman Brown,” featuring suspected witches and some dark secrets, and a lot of great lines.

“Such company, thou wouldst say,” observed the elder person, interpreting his pause. “Well said, Goodman Brown! I have been as well acquainted with your family as with ever a one among the Puritans; and that’s no trifle to say. I helped your grandfather, the constable, when he lashed the Quaker woman so smartly through the streets of Salem. And it was I that brought your father a pitch-pine knot, kindled at my own hearth, to set fire to an Indian village, in King Philip’s war. They were my good friends, both; and many a pleasant walk have we had along this path, and returned merrily after midnight. I would fain be friends with you, for their sake.”

Or this observation:

The fiend in his own shape is less hideous, than when he rages in the breast of man.

A literal devil isn’t really necessary, except as a scapegoat. Humans are capable of appalling evil all by ourselves. In the climactic scene, where (spoiler) the pillars of the town are revealed as a bunch of devil-worshipers, the person leading the ritual explains.

“There,” resumed the sable form, “are all whom ye have reverenced from youth. Ye deemed them holier than yourselves, and shrank from your own sin, contrasting it with their lives of righteousness, and prayerful aspirations heavenward. Yet, here are they all, in my worshiping assembly! This night it shall be granted to you to know their secret deeds; how hoary-bearded elders of the church have whispered wanton words to the young maids of their households; how many a woman, eager for widow’s weeds, has given her husband a drink at bed-time, and let him sleep his last sleep in her bosom; how beardless youths have made haste to inherit their fathers’ wealth; and how fair damsels - blush not, sweet ones - have dug little graves in the garden, and bidden me, the sole guest, to an infant’s funeral. By the sympathy of your human hearts for sin, ye shall scent out all the places - whether in church, bed-chamber, street, field, or forest - where crime has been committed, and shall exult to behold the whole earth one stain of guilt, one mighty blood spot…Lo! there ye stand, my children, depending upon one another’s hearts, ye had still hoped, that virtue were not all a dream. Now ye are undeceived! Evil is the nature of mankind. Evil must be your only happiness. Welcome, again, my children, to the communion of your race!”

Man, that’s depressing. And kind of hard to disagree with right now. Apparently, this story stuck with me, because I wrote down more from it than any other story.

Hawthorne’s son Julian also contributes a story to the book, “Absolute Evil,” a supernatural tale involving a recluse couple on a barrier island, a girl orphaned by a shipwreck, and a bit of lycanthropy. Julian’s own life story is a bit lurid, with him spending a year in prison for his role in a stock fraud, followed by his complaint that prison was inhumane punishment. (He may have been right, but it sure seems like the January 6 insurrectionists complaining about prison conditions.)

Another author with an interesting story was Emma Francis Dawson. “An Itinerant House” was one of my favorites in the book, with a house seemingly cursed and leading to the suicides of those who occupy it - even after the house is first abandoned, then torn down and a room reassembled elsewhere. Dawson herself struggled to support herself, despite her writing talent, and is believed to have starved to death due to poverty.

I should also mention a particularly chilling story by Herman Melville, “The Tartarus of Maids.” Those familiar with Greek mythology will understand that this is a vision of hell. The form of that hell is a paper factory employing young girls - so one might consider this to be a very realistic tale of horror.

I earlier mentioned “The Yellow Wall Paper,” which is a total classic. Much has been written about its themes, so I won’t get into that here. I did want to mention that, although I had read it before - quite some time ago - I had forgotten some of the details, which is how I missed just how much Mexican Gothic by Silvia Morano-Garcia owes to Gilman’s short story. There are a lot of intentional nods to the earlier story throughout the novel, even if the plot goes in a rather different direction. (While retaining the feminist themes.)

Another story that intrigued me was “Thurlow’s Christmas Story” by John Kendrick Bangs. It had some interesting parallels with The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, so I had to check which came first. (Stevenson did it first, as it turns out.) Particularly imaginative in this case is the ending, after we discover that the story that the mysterious stranger leaves turns to blank pages. The fictitious writer has been relating the crazy tale to that point as an explanation to the editor as to why he sent in blank pages. The editor’s response is amusing.

Your explanation has come to hand. As an explanation it isn’t worth the paper it is written on, but we are all agreed here that it is probably the best bit of fiction you ever wrote. It is accepted for the Christmas issue. Enclosed please find check for one hundred dollars.

One of the weirdest stories is by Robert W. Chambers, “The Repairer of Reputations.” It is pretty long, and involves a dystopic future United States, when all minorities have been placed on reservations or evicted, but that isn’t really what the story is about. And for that matter, what even is it about? Well, the narrator is admittedly mentally ill with brain damage from an accident. And by the end, it is nearly impossible to tell what - if anything - he has told the reader is actually true. Apparently, the story is part of a collection with a lot of interconnections centered around The King in Yellow, a fictional play whose “quotes” are found throughout the stories. Apparently, the play has been banned, because it induces despair or madness in all who read it.

I made a note of a line in “The Striding Place” by Gertrude Atherton. The story itself is a fairly short horror or possibly ghost story. It is the description that I found interesting. This story, like a number of them, are set in places other than America.

An English wood is like a good many other things in life - very promising at a distance, but a hollow mockery when you get within. You see daylight on both sides, and the sun freckles the very bracken. Our woods need the night to make them seem what they ought to be - what they once were, before our ancestors’ descendants demanded so much more money, in these so much more various days.

There is a Henry James story in here - he wrote quite a few spooky tales, not just The Turn of the Screw. “The Jolly Corner” manages to be both a really creepy (and suspenseful) ghost story, and a love story of sorts. And also, very much of a Henry James sort of thing. If you know, you know. James was an incredible observer of human behavior, and his rather sharp comments on the things people do are fascinating. Here is one aside about the protagonist.

He was a dim secondary social success - and all with people who had truly not an idea of him. It was all mere surface sound, this murmur of their welcome, this popping of their corks - just as his gestures of response were the extravagant shadows, emphatic in proportion as they meant little, of some game of ombre chinoises.

I was more surprised to find a ghost story by Edith Wharton, who is better known for her realistic novels about high New York society. “Afterward” is indeed a fairly long and carefully plotted ghost story. It starts with Mary Boyne about to go with her husband to live in England on his new fortune, and wanting to find a haunted old house to stay in. Which they do, except that she can’t seem to see any ghosts. However, as her friend Alida says, the ghost at Lyng is peculiar in that you will never know you saw it, until afterwards. (Hence the title of the story.) As the story progresses, it becomes clear that Mary’s husband has been hiding some of his financial affairs, including a lawsuit from a man claiming to have been defrauded. There is a particular line that I thought was fun. Alida has recommended Lyng - which is owned by her husband’s cousins - as being available for very low cost.

The reason she gave for its being obtainable on these terms - its remoteness from a station, its lack of electric light, hot water pipes, and other vulgar necessities - were exactly those pleading in its favour with two romantic Americans perversely in search of the economic drawbacks which were associated, in their tradition, with unusual architectural felicities.

Willa Cather, another author more associated with realistic writing, also contributes a ghost story to this book, and it is a rather peculiar and memorable one. The narrator’s friend finds himself haunted by some sort of ghost or specter that has glommed on to him after they meet on a rainy night. Cather uses the story to explore the question of why people who seem to have no cause will commit suicide. A paraphrase attributed to Samuel Johnson is a fascinating bit. I wasn’t able to verify the original source online, so I have no idea if Cather’s characters are getting it right, or misattributing, or whatever.

It reminds me of what Dr. Johnson said, that the most discouraging thing about life is the number of fads and hobbies and fake religions it takes to put people through a few years of it.

Once we get into the pulps, the stories become even more lurid. The writing is a bit more uneven, but overall, Straub chooses the best of the bunch, rather than the dreck.

A characteristic tale is by Francis Stevens, “Unseen - Unfeared.” In it, a mad scientist (in the more literal than figurative sense) accidentally creates a lens that shows that the world is occupied by unseen and horrifying creatures, all of them created by the evil that indwells mankind.

Also memorable is “The Jelly-Fish,” by David H. Keller, a short yet disconcerting tale. This mad scientist claims that humans can do anything - even impossible things - with enough willpower. And, to prove it, he shrinks himself to a small size and attempts to communicate with a jellyfish. Which eats him.

I will also mention a story I had read before, but still love, “The King of the Cats” by Stephen Vincent Benet - an underrated author in my opinion.

A number of the authors had stories that were almost as lurid as what they wrote. Conrad Aiken discovered the bodies of his parents as a young boy - his father murdered his mother than shot himself. Robert E. Howard killed himself as his mother lay dying. (Not from murder, at least.) Seabury Quinn specialized in mortuary law.

It was necessary to include an H. P. Lovecraft story, of course. The history of horror would not be complete without him. Still, the man was viciously racist, and that comes through in his writings, unfortunately. There was also a sour note in his story, “The Thing on the Doorstep,” an otherwise good tale, regarding women. (Ironically, it appears on page 666 of the book.) The evil spirit of this nasty old guy has essentially possessed the body of his daughter, and is now trying to get at the narrator’s friend.

The worst thing was that she was holding on to him longer and longer at a time. She wanted to be a man - to be fully human - that was why she got hold of him. She had sensed the mixture of fine-wrought brain and weak will in him. Some day she would crowd him out and disappear with his body - disappear to become a great magician like her father and leave him marooned in that female shell that wasn’t even quite human.

Yeesh, that’s bad. And this was written less than 100 years ago. Plenty of the other stories in the book, even those written by men 100 years prior, were more respectful of women, and portrayed them as fully human. It certainly doesn’t make me eager to read anything else by Lovecraft.

The final bit comes from the last story, “The Cloak,” a vampire tale by Robert Bloch. You might know him as the author of Psycho, which was made into a little movie by a guy named Hitchcock. The opening bits of the story are hilarious - purple prose at its most mauve. As it turns out, this is intentional: the protagonist is under the influence of halloween, and can’t stop thinking in overwrought terms.

The sun was dying, and its blood spattered the sky as it crept into a sepulcher behind the hills. The keening wind sent the dry, fallen leaves scurrying toward the west, as though hastening them to the funeral of the sun.

I started reading this book back in October, and just read a bit here and there when I felt like it. With over 700 pages, it took a while, and I probably don’t remember the earlier stories as freshly as if I had written about them then. It is a good collection, though, and I look forward to reading volume two eventually.

To contextualize the Lovecraft: the antagonist was from Innsmouth, a village which had engaged for generations in interbreeding with some sort of sea-devil creature. When the narrator's friend raves that she isn't fully human, he means exactly that.

ReplyDeleteExcept that in the same passage, he is clearly indicating that the supernatural creature wants out of the sub-human female and into the more fully human male creature.

Delete