Source of book: I own this.

About five years ago, I read The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran’s most famous work. Since then, I have collected several other volumes of his work, typically for next to nothing at library sales.

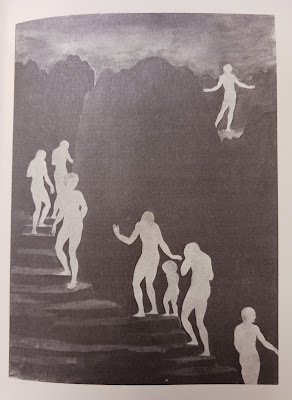

One of the original illustrations by the author.

Because I gave a good bit of biographical information in the previous post, I won’t repeat it here. I do recommend The Prophet as a good place to start with Gibran.

A Tear and a Smile is not, like The Prophet, a single work. Rather, it is a collection of Gibran’s early writings in Arabic, written when he was in his twenties, just starting out as a writer. What ties the collection together is not so much a theme as the time in which they were written. Thus, the volume ends with a collection of songs, starts with title essay, and contains both poetry and prose in addition to the beginnings of the “prose-poetry” that his mature work would be characterized by.

Like most juvenalia, the quality is a bit uneven. Gibran is starting to find his voice, but is still trying on some different ideas. Probably the greatest flaw is the tendency in some of the essays to be very black and white in his thinking, showing the earnestness and lack of nuance of youth. Compared with his later work, it feels a bit rough, a bit judgmental, and a bit simplistic. However, you can see the trend toward his maturity. Alongside the rougher stuff, there are also beautiful poems, thoughtful musings on what really matters in life, pointed observations on the moral corrosion of wealth, and flights of mystical lyricism.

I think the introduction by Robert Hillyer is illuminating:

Like those of many romantic poets, his youthful flights were toward the white radiance of eternity, away from a world that seemed largely in the hands of injustice and violence. The recoil of a sensitive mind from reality frequently takes revolutionary forms of which political revolution is merely the most obvious. With Gibran, the revolt was not directed toward institutions so much as toward the individuals who became the accomplices of abstract evil, of greed, injustice, and bloodshed. Most of the human figures in his early works are therefore personifications, with the result that parable and allegory are the usual method.

To view these early works in that light is helpful. All sensitive minds recoil from the injustice in the world - and find themselves frustrated with the individuals who seem to be so willing to be accomplices of evil. This is the core of why I left organized religion six years ago. There is no place for a sensitive mind, for someone who recoils at injustice rather than excuses it, and who cannot stay silent while others spew violence, greed, and hatred toward the most vulnerable in our society. The role of the poet as prophet and conscience of the community is an important one, and one that is currently rather out of style in our society. One of my favorite poems in the collection is about that very thing.

The Poet

A link

Between this world and the hereafter;

A pool of sweet water for the thirsty;

A tree planted

On the banks of the river of beauty,

Bearing ripe fruits for hungry hearts to seek.

A singing bird

Hopping along the branches of speech,

Trilling melodies to fill all bodies with sweetness and tenderness.

A white cloud in the sky at even,

Rising and expanding to fill the heavens,

And then pour out its bounty upon the flowers of the fields of Life.

An angel

Sent by the gods to teach man the ways of gods.

A shining light unconquered by the dark,

Unhidden by the bushel

Astarte did fill with oil;

And lighted by Apollo.

Alone,

He is clothed in simplicity

And nourished by tenderness;

He sits in Nature’s lap learning to create,

And is away in the stillness of night

In wait of the spirit’s descent.

A husbandman who sows the seeds of his heart in the garden of feeling,

Where they bring forth yield

To sustain those that garner.

This is the Poet that is unheeded of men in his days,

And is known by them on his quitting the world to return to his heavenly abode.

This is he who seeks no thing of men save a little smile;

Whose breath rises and fills the firmament with living visions of beauty.

Yet do the people withhold from him sustenance and refuge.

Until when, O Man,

Until when, O Existence,

Will you build houses of honor

To them that knead the earth with blood

And shun those who give you peace and repose?

Until when will you exalt killing

And those who make bend the neck beneath the yoke of oppression?

And forget them that pour into the blackness of night

The light of their eyes to show you the day’s splendor?

Those whose lives are passed in misery

That happiness and delight might not pass you by.

And you, O Poets,

Life of this life:

You have conquered the ages

Despite their tyranny,

And gained for you a laurel crown

In the face of delusion’s thorns.

You are sovereign over hearts,

And your kingdom is without end.

What particularly resonated with me about this poem is the way that our human society tends to glorify and exalt soldiers and militarists. I understand the dilemma that leads to a perceived need for soldiers - as long as evil and narcissistic men have access to weapons (from Hitler to Putin and so many in between), there will be a need to protect the innocent from aggression. But to glorify those who start wars, who invade their neighbors, who pursue “glory” utilizing the lives of younger men? We have no business exalting them. Rather, we should be glorifying the healers, the teachers, those who create life and beauty rather than destroying it. Anyone can destroy. Creation and healing is a lot more work.

The title essay is in the form of the sort of prose-poetry that The Prophet utilizes so well. I thought it was a good description of the experience of being a sensitive and compassionate human.

I would not exchange the sorrows of my heart for the joys of the multitude. And I would not have the tears that sadness makes to flow from my every part turn into laughter. I would that my life remain a tear and a smile.

A tear to purify my heart and give me understanding of life’s secrets and hidden things. A smile to draw me nigh to the sons of my kind and to be a symbol of my glorification of the gods.

A tear to unite me with those of a broken heart; a smile to be a sign of my joy in existence.

I would rather that I died in yearning and longing than that I lived weary and despairing.

I want the hunger for love and beauty to be in the depths of my spirit, for I have seen those who are satisfied the most wretched of people.. I have heard the sigh of those in yearning and longing, and it is sweeter than the sweetest melody.

With evening’s coming the flower folds her petals and sleeps, embracing her longing. At morning’s approach she opens her lips to meet the sun’s kisses.

The life of a flower is longing and fulfillment. A tear and a smile.

The waters of the sea become vapor and rise and come together and are a cloud.

And the cloud floats above the hills and valleys until it meets the gentle breeze, then falls weeping to the fields and joins with the brooks and rivers to return to the sea, its home.

The life of clouds is a parting and a meeting. A tear and a smile.

And so does the spirit become separated from the greater spirit to move in the world of matter and pass as a cloud over the mountain of sorrow and the plains of joy to meet the breeze of death and return whence it came.

To the ocean of Love and Beauty - to God.

The bittersweetness of life and love and beauty.

In a prose essay, “A Vision,” which is, according to Gibran, a public response to a letter from a viscountess, he envisions Youth and Man and a host of other allegorical figures, as he surveys the wreckage of humanity. There is one line in there that stood out to me.

I beheld priests, sly like foxes; and false messiahs dealing in trickery with the people. And men crying out, calling upon wisdom for deliverance, and Wisdom spurning them with anger because they heeded not when she called them in the streets before the multitude.

This is an accurate summary of the Trump Era in American Evangelicalism. But more than that, it is a timeless observation about wisdom. It is easy to forget that in Proverbs, the two women are both allegorical. Wisdom is a woman, of course. But so is her opposite, “the adulteress” - otherwise known as Folly. In our Puritan hangover in the English-speaking world, we have debased Folly into a literal adulteress - those crafty oversexed women lying in wait for innocent men, whose penises find themselves magically outside their pants. (Hence the absolution granted to every celebrity pastor who commits clergy sexual abuse - it’s always her fault.)

But I digress. The iconic moment in Proverbs involving Wisdom is that she is calling out in the streets.

Out in the open wisdom calls aloud, she raises her voice in the public square; on top of the wall she cries out, at the city gate she makes her speech: “How long will you who are simple love your simple ways? How long will mockers delight in mockery and fools hate knowledge? Repent at my rebuke! Then I will pour out my thoughts to you, I will make known to you my teachings. But since you refuse to listen when I call and no one pays attention when I stretch out my hand, since you disregard all my advice and do not accept my rebuke, I in turn will laugh when disaster strikes you; I will mock when calamity overtakes you— when calamity overtakes you like a storm, when disaster sweeps over you like a whirlwind, when distress and trouble overwhelm you. “Then they will call to me but I will not answer; they will look for me but will not find me, since they hated knowledge and did not choose to fear the LORD. Since they would not accept my advice and spurned my rebuke, they will eat the fruit of their ways and be filled with the fruit of their schemes. For the waywardness of the simple will kill them, and the complacency of fools will destroy them; but whoever listens to me will live in safety and be at ease, without fear of harm.”

Gibran remixes this (as he does passages from the Hebrew scriptures, the New Testament, and the Koran) in a memorable way. The key point is this: Wisdom has been calling in the streets, but people love Folly more. They reject wisdom and reject wisdom and reject wisdom until disaster overtakes them.

This has been the pattern of Evangelicalism for decades. They have rejected wisdom because it doesn’t solely come from inside the tribe. The leaders have embraced the idea that science is an atheist conspiracy, medicine is an atheist conspiracy, mainstream history is an atheist conspiracy (and a “woke” conspiracy…) and so on. Then, when a pandemic hits, basic public health measures from masks to avoiding gatherings to vaccines become “oppression” and instead quack cures and racist conspiracy theories are embraced.

And don’t get me started on the false (and very orange) messiah.

On a related note, the brief essay, “Before the Throne of Beauty,” illuminates another facet of what has gone badly wrong in American religion.

And on her lips was the smile of a flower and in her eyes the hidden things of life. She said: “You, children of the flesh, are afraid of all things, even yourselves do you fear. You fear heaven, the source of safety. Nature do you fear, yet it is a haven of rest. You fear the God of all gods, and attribute to Him envy and malice. Yet what is He if not love and compassion?”

This is an observation my wife and I have been discussing a lot lately. She is now manager of the ICU units at her hospital, and has had to deal with even more of the most difficult family situations. What is shocking and inexplicable is that those who most claim to believe in an afterlife (of whatever kind - this transcends any one religion, eastern or western - it seems to afflict the most devout of all sorts) are the ones most terrified of death, particularly the death of a loved one. In one recent case, a family was threatening lawsuits for supposed poor care, because their family member died.

Said family member was in their 90s.

The fear runs so deep. I do not think it is “even yourselves” as “particularly yourselves.” To be so afraid of one’s self that you cannot trust your own conscience? Your own body? To be so suspicious of anything that doesn’t come from whatever charlatan you decide has the very words of God for you? I cannot fathom how deeply soul-crushing such an existence must be.

In another short essay, “O My Poor Friend,” Gibran laments those who suffer under systems of oppression. One paragraph was particularly fascinating.

O soldier who is sentenced by man’s cruel law to forsake his mate and his little ones and kin to go out on the field of death for the sake of greed in its guise as duty.

This applies to so many soldiers, including those we traumatized in Vietnam for the sake of geopolitical proxy wars. I can’t help but think of the conscripted Russian soldiers right now, becoming cannon fodder for Putin’s ambitions of Empire. So many wars are nothing more than greed disguised as duty or country.

One of the most beautiful prose-poem essays is “My Birthday,” composed for the 25th birthday of the poet. Gibran reflects on who he is, and who he hopes to be. This one paragraph is breathtaking:

I have loved freedom, and my love has grown with the growth of my knowledge of the bondage of people to falsehood and deceit. And it has spread with my understanding of their submission to idols created by dark ages and raised up by folly and polished by the touch of adoring lips.

Me too, Kahlil, me too.

The final section consisting of songs is the most consistently good poetry in the book. I was torn as to which to feature in this post. There are odes to waves and rain and beauty and happiness and flowers. There is even one to humanity and the human spirit. It concludes with “A Poet’s Voice,” a prose-poem that is too long to quote other than a passage or two. (See below.) I decided to go with this one:

A Song

In the depths of my spirit is a song no words shall clothe;

A song living in a grain of my heart that will flow not as ink on paper.

It encompasses my feeling with a gossamer cloak,

And will not run as moisture on my tongue.

How shall I send it forth even as a sigh

Whilst I fear for it from the very air?

To whom shall I sing it that knows no dwelling

Save in my spirit?

I fear for it from the harshness of ears.

Did you look into my eyes, you had seen the image of its image;

Did you touch my fingertips, you had felt its trembling.

The works of my hand reveal it

Even as the lake mirrors the shining stars.

My tears disclose it

Even as dewdrops that proclaim the rose’s secret as the warmth scatters them.

A song sent forth of silence,

Engulfed by clamor

And intoned by dreams.

A song concealed by awakening.

O people, ‘tis the song of Love;

What Ishak shall recite it?

Nay, what David shall sing it?

Its fragrance is sweeter than the jasmine’s;

What throat shall enslave it?

More precious is it than the virgin’s secret;

What stringed instrument shall tell it?

Who shall unite the sea’s mighty roar

With the nightingale’s trilling?

And the sigh of a child with the howling tempest?

What human shall sing the song of the gods?

I want to close with an observation from “A Poet’s Voice.”

I see myself as a stranger in one land, and an alien among one people. Yet all the earth is my homeland, and the human family is my tribe. For I have seen that man is weak and divided upon himself. And the earth is narrow and in its folly cuts itself into kingdoms and principalities.

The core insight here is this. Humankind isn’t so much divided between its members as it is divided upon itself. It is as if a man chopped himself to pieces - a self-dissection. We are not drawing the lines between us and them. In reality, we are cutting ourselves off from ourselves, trying to pretend that this leg or this lobe of the heart isn’t part of ourselves too. This is the central tragedy of humanity - our original sin, so to speak. (A less blockheadedly literalist reading of Genesis reveals that truth. We are squinting so hard to see Genesis as literal history that we miss the way the Fall led inexorably to the first murder, until the whole earth was filled with violence and injustice.) This puts the teachings of Christ in a different light than the narrow minded and withered-hearted spiritualization that they have been given by Evangelical doctrine, doesn’t it? The reconciliation of all things - the Kingdom of Heaven, neighbor-and-enemy love, the fury at the commercialization of religion - it is all about undoing that fatal self-dissection of greed, us-versus-them, and human tribalism.

A Tear and a Smile isn’t as universally good as The Prophet, but it has its thrilling moments. Gibran’s mature writings show the effect of time and experience on the best of his ideas, but you can see the seeds in his early writings.