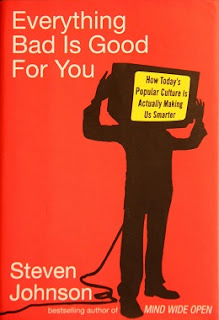

Source of book: Borrowed from the library

Tell me if you have heard this before:

“Pop culture keeps getting more and more stupid.”

“It’s a race to the bottom.”

“Things were so much better in the past.”

Yeah, me too.

The thing is, that is completely wrong.

I have read a few books that touch on this theme over the years. Steven Pinker’s outstanding deep look at historical violence, The Better Angels of Our Nature, examined the evidence that violence has dramatically declined over time. Frank Kermode examined why human nature tends to believe in a golden past and a decadent present (as well as a future apocalypse and return of the golden age) in The Sense of An Ending. You can see it in many other areas too. While history isn’t a straight line, we are living in a far more humane present than the supposedly glorious past.

But, even among those who believe in a notion of progress, it seems to be taken as unquestionably true that pop culture is more stupid than it used to be.

This too, however, does not stand up to the actual evidence.

What has happened is that culture has changed. Which it always has done. And along with change, there has always been whining about cultural decline. Always, as in “from the first time people wrote stuff down, they whined about the next generation and its trash culture.”

Kermode has a pretty good take on some of the issues, but I think that an easy way to understand the phenomenon is that when we remember the past, we remember the good and great stuff. There are two ways this works. First is the way we remember things from our childhood as wonderful and amazing and super. Many of those things - movies or shows we loved - haven’t aged as well as we thought they would. I can think of a few that were a lot of fun at age 5, but are unwatchable now.

The other way this works, though, is that we remember the good stuff, and forget the dreck. Most English-speakers are familiar with Charles Dickens, for example. Great writer (although flawed), had a fairly large following for his time (although by percentages, it was still a really elitist phenomenon - by modern standards, he would have a very niche audience), wrote arguably the best story of all time. But how many remember the “penny dreadfuls,” or the preachy dreck that passed for children’s literature in the Victorian Era? And let’s not think too much about Elsie Dinsmore. And so it has been for any era. Most of the trash exists in its moment, then disappears from memory. And thus we forget it, and remember only the best of what was.

The end result of this is that usually, when someone talks about how bad culture is compared to the past, they compare the best of the past to the worst of the present. Naturally, the present doesn’t come off too well. As Johnson puts it, the relevant comparison is not between Joe Millionaire and M*A*S*H; it is between Joe Millionaire and The Price is Right.

I learned a new name from this book: Marshall McLuhan. Apparently, he was popular among the intelligentsia back in the day. He gets a quote at the beginning of the first part, and, I think he nails it.

“The student of media soon comes to expect the new media of any period whatever to be classed as pseudo by those who acquired the patterns of earlier media, whatever they may happen to be.”

That is the phenomenon I mentioned at the start of this post. The way each generation looks down on the next generation’s form of culture and media.

Steven Johnson takes an interesting approach to this idea, and starts looking at empirical evidence. In the first half of the book, he examines pop culture - television, video games, movies, the internet, etc. - and looks for signifiers of complexity. He makes a great case that in all of these areas, the complexity level has gone way up - and “difficult” media are more popular than ever. In the second, he looks at specific measures of intelligence that appear to be affected by this increased complexity, and shows that it has been increasing over time.

Whether or not you find Johnson’s argument convincing as to his claim that pop culture has actually made humans measurably smarter, he makes a solid case that the claim that culture has gotten stupider is just straight up balderdash.

Johnson starts the book with a story that I found intriguing. He describes a complex baseball simulation game he used to play - the American Professional Baseball Association. This game was played using cards with conversions of stats to represent every skill level for every player. It was incredibly complex, and sounds like a real slog to play.

Except that my brother and I kind of did, as kids. Not exactly - we didn’t have a commercial game, and what we played wasn’t that complex. Instead, we ourselves invented a simpler version that used dice and stats. We were, I believe, in 5th and 7th grade at the time. And yes, it was a slog to play, yet we enjoyed it and spent hours at it.

This sets up one of Johnson’s key assertions - and I think that he is 100 percent correct:

Human nature is NOT to seek the lowest common denominator for entertainment. Rather, humans seek challenges and new experiences.

This book is, ultimately, the story of how the kind of thinking I was doing on my bedroom floor became an everyday component of mass entertainment. It is the story of how systems analysis, probability theory, pattern recognition, and - amazingly enough - old-fashioned patience became indispensable tools for anyone trying to make sense of modern pop culture. Because the truth is my solitary obsession with modeling complex simulations is now ordinary behavior for most consumers of digital age entertainment.

For decades, we’ve worked under the assumption that mass culture follows a steadily declining path toward lowest-common-denominator standards, presumably because the “masses” want dumb, simple pleasures and big media companies want to give the masses what they want. But in fact, the opposite is happening: the culture is getting more intellectually demanding, not less.

Watching my kids and their friends in action over the last two decades, I understand what Johnson means. The kids can keep complex worlds in their heads, solve pattern problems quickly, and are able to think at a level of nuance that I have only rarely found among my parents’ generation. (And I think this is directly related to the way their era of television demanded little thought, and reduced everything to black-and-white thinking.)

Speaking of which, there is a passage in the section on television that really made sense. In it, Johnson describes the use of “flashing arrows,” cues that tell the viewer things about what is going on. In the movie Student Bodies, a slasher parody, these are literally flashing arrows saying things like “door unlocked” or “bad guy.” This is an exaggeration for humor, of course, but Johnson notes that these cues are everywhere in the first few generations of television and movies. Things are spelled out for the viewer, and are usually not subtle. The label of “bad guy” and “good guy” are particularly in use at all times. (This still happens, of course - there is still terrible television like copaganda shows, for example, with oversimplistic thinking and lots of flashing arrows.)

This got me thinking about the way that modern politics (particularly on the right) have manipulated those raised on this sort of television. A demagogue like Trump simply taps into the flashing arrows people already expect to see. These people are bad, these people are good. We are the good people. They are the bad people. See that flashing arrow? I think this is one element of the appeal to certain demographics - the techniques of my parents’ generation of television are so ingrained as to be useful tools for preventing careful thought and empathy.

I should confess here that I am not much of a watcher of television or movies, and I never did get into any video games that required hand-eye coordination. I did, however, enjoy the brain games - particularly SimCity, which gets a few mentions here as one of the first games where learning complex systems in an open-ended way was the whole point of the game. (It also played a role in my eventual rejection of right-wing economic theories - clearly taxes and public infrastructure were necessary. And you couldn’t just build more police stations if you didn’t address the other causes of crime.)

Because of my lack of TV watching, I didn’t have the background knowledge for some of his show discussions (although his summaries are excellent and helpful), but I was able to understand his analogies to other media. I liked his comparison of a Seinfeld plot where the scenes are played in a backwards chronology to a Harold Pinter play.

Another thing Johnson says that makes sense is that past media tended to have fixed rules that everyone understood. Now, the rules aren’t clear, but are discovered as you play the game, so to speak. The difference between Pac Man and Myst, or between Wheel of Fortune and Chopped. I have noticed this with my kids too - as Johnson notes later in the book, they do not need a manual to figure out how to program the streaming device or other electronic stuff. They instinctively know how to learn a new set of rules, even unintuitive ones. They have been trained to figure the rules out as they go.

Another fascinating observation is that modern media makes greater demands on emotional intelligence. Reality shows, for example, are not about solving puzzles so much as they are about navigating complex social situations. One of the ongoing arguments over homeschooling is “socialization” - and I think this is where the weakness can tend to be. It is one thing to exist in a family or small group, but learning how to navigate larger social systems is an important skill. I think that there is a genuine risk if children (or adults) exist in a small bubble of similar people. Which is what happens in some homeschooling subcultures. My own experience was different: we had neighborhood kids over all the time, and participated in extracurricular activities across a fairly broad range of groups. We were not sheltered in that sense, but had opportunities to see different group dynamics. I do like Johnson’s thoughts on emotion and intellect.

Television turns out to be a brilliant medium for assessing other people’s emotional intelligence or AQ - a property that is too often ignored when critics evaluate the medium’s carrying capacity for thoughtful content. Part of this neglect stems from the age-old opposition between intelligence and emotion: intelligence is following a chess match or imparting a sophisticated rhetorical argument on a matter of public policy; emotions are the province of soap operas. But countless studies have demonstrated the pivotal role that emotional intelligence plays in seemingly high-minded areas: business, law, politics. Any profession that involves regular interaction with other people will place a high premium on mind reading and emotional IQ.

And also this:

[L]ike many forms of emotional intelligence, the ability to analyze and recall the full range of social relationships in a large group is just as reliable a predictor of professional success as your SAT scores or your college grades. Thanks to our biological and cultural heritage, we live in large bands of interacting humans, and people whose minds are skilled at visualizing all the relationships in those bands are likely to thrive, while those whose minds have difficulty keeping track are invariably handicapped.

I also liked Johnson’s discussion of IQ tests. He starts by dealing with the obvious issue: the tests are biased toward those with certain cultural and educational backgrounds. For Johnson, this means that tests are of little value in making comparisons between different demographic groups. There are differences in both genes and environments, so drawing conclusions about genes often ignores the environments.

In contrast, Johnson believes that there is value in IQ tests when used for comparisons of the same population. The test scores are adjusted so that 100 represents average intelligence. In order to keep this the case, the scores have to be “scaled.” And over time, this means that raw scores have risen even as the numerical scores by definition remain the same.

Or, simply put, scores are going up. People are getting smarter, at least the way the tests measure intelligence. (Johnson further notes that the big increase in scores is in areas that would seem to be related to the increased complexity in media - that discussion is too long for this post.)

For Johnson, the key takeaway from this is that, since the gene pool has stayed the same, it isn’t the genes causing the increase - it is the environment. Furthermore, since academic test scores are not going up at that rate, it is unlikely that it is formal schooling which is getting better. More likely, it is something elsewhere in the culture. The education is occurring outside the classroom.

It certainly is an interesting thought. I will end with this one, which I think is the most true assertion in the book, the one that debunks the myth of declining intelligence.

The Brave New World critics like to talk a big game about the evils of media conglomerates, but their worldview also contains a strikingly pessimistic vision of the human mind. I think that dark assumption about our innate cravings for junk culture has it exactly backwards. We know from neuroscience that the brain has dedicated systems that respond to - and seek out - new challenges and experiences. We are a problem-solving species, and when we confront situations where information needs to be filled in, or where a puzzle needs to be untangled, our minds compulsively ruminate on the problem until we’ve figured it out.

I should mention that this book was published in 2005, so it isn’t exactly up to the present on shows and movies and stuff, but I think the trends he describes have continued, even if the specifics are now different. And the kids are even better at the electronics than he expected.

***

My teens and I have enjoyed a few other Steven Johnson books over the years. Here is the list: